By Aðalsteinn Kjartansson and Heli Seljan

23 October 2024

Technicians on behalf of the District Prosecutor’s Office recently managed to recover another thousand text messages that were sent between Þorstein Más Baldvinsson and Jóhannes Stefánsson, while the latter was working in Namibia. The message paints a very different picture than the CEO and other company spokespeople have tried to paint over the past five years.

“I had nothing to do with the man,” said Þorsteinn Már Baldvinsson, CEO of Samherji, in a hearing at the district

attorney’s office in the summer of 2020, about his relations with Jóhannes Stefánsson, managing director of Samherji’s shipping company in Namibia. When the investigators approached him and asked if there had been any contact between them, he agreed, but specifically stated that it had been “in a limited way”. It does not match the discovery that researchers at the same office have now made.

Thousands of short messages that were sent and received on the mobile phone of Jóhannes, an informant in the Samherja case, were recently found on a computer that Jóhannes handed over to the district attorney in 2019.

According to the source’s information, Jóhannes’s computer had taken a backup of the phone, around or after the time that Jóhannes retired from Samherji. Police experts seem to have realized this and managed to recover text messages that had been copied. They show a different picture of Jóhannes’ relations with the CEO and other employees of Samherji than the Samherji representatives have publicly claimed.

Jóhannes was working in Namibia for five years, from 2011 to 2016, and the message spanned the majority of that time. According to the source’s information, they shed new light on the relationship between Jóhannes and Þorstein Más, in relation to the relationship between Samherji and Namibian rulers. The latter have been in custody and are awaiting trial for having accepted payments of up to two billion ISK from Samherja, who in return enjoyed few special benefits and access to valuable fishing permits.

In total, the SMS messages between Þorstein and Jóhannes are over 1,500, according to the source’s information.

It is almost equivalent to the fact that one message passed between them every single day that Jóhannes was working in Namibia.

This is in stark contrast to the previous statement of Þorstein Más, who has often and repeatedly claimed that he had no involvement or contact with Jóhannes, while the latter managed the Samherji trawler company in Namibia, which was already heavily hunted and over a quarter of the nation’s horse mackerel quota, up to one hundred thousand tons, every year.

“The communication was really, really limited, but he was obsessed with sending completely endless emails, which at the time were actually little read,” said Þorsteinn during a hearing by the district attorney in 2020. “I had limited communication with this man.”

Either too much or too little

This was the company’s defense in YouTube videos that were produced after the disclosure of the Samherja case. There, both CEOs of Samherja, Þorsteinn Már, and Björgólfur Jóhannsson, stated that the operation in Namibia was in practice irrelevant to everyone; except Jóhannes Stefansson.

“It is quite clear that the former manager managed the business from A to Z. There was far too little knowledge of what was going on in Namibia within Samherji’s high command. There really weren’t any devices like this that gave someone a clue that something was wrong,” said Björgólfur in one of these videos.

Þorsteinn Már said his only responsibility was not to have followed. “Samherji’s mistake is not having better control over the operations in Namibia and, as a result, a better overview.” And I do not shy away from the responsibility that I bear in that regard,” he said in the same video. “We have always shown confidence in Samherji’s management.”

When Þorsteinn Már attended his first hearing at the district

prosecutor’s office regarding the investigation of the bribery case, he also pretended that he actually knew little about Jóhannes. He was never his boss and he repeatedly tells the investigators that he really had no reason to communicate with him.

During the hearing, however, he complained about the constant stream of information that came from Johannes. “I’m just saying that the man sent maybe twenty, thirty emails and everyone was asking him to stop this and something like that and, so I’m saying that I had limited communication with this man,” Þorsteinn told researchers, but reiterates that these posts have been little read.

Already tried SMS?

Jóhannes said as soon as he stepped forward in the coverage of Kveik og Stundinar, which was done in collaboration with Wikileaks, in 2019, that Þorsteinn wanted to talk to him through video calls rather than by other means.

“I didn’t pay any bribes without getting the green light from Þorstein. I just got the information and I contacted Þorstein and said: They have requested to get this aside as a bribe and can I get green from you? And it was then only given a green light. But it was never in any mail communication, but through Skype or through video conference in his office or the office in Namibia, because it is a safe way of communication.”

According to the source’s information, many of the text messages that Þorsteinn sent to Jóhannes were about organizing such video conference meetings. Heimildin’s journalists have previously received a description of these meetings. Þorsteinn appeared on the screen but tended to be quiet and instead nodded his head as a sign of approval.

In the aforementioned YouTube videos, Þorsteinn said these explanations by Jóhannes as a sign that he knows that there is nothing documented that implicates him in bribe payments.

“Jóhannes knows that there are no e-mails that show instructions to pay bribes. That’s why he says I gave the instructions in a different way. Jóhannes Stefánsson is wrong. I have given no such instructions.”

Björgólfur, who temporarily took over Þorstein’s director’s chair after the authorities’ investigation began, said in the same video that he had found nothing in writing about bribery, despite extensive searches. “No data has been found, we have reached something over a million documents that have been examined,emails, the relevant employee’s cell on his computer and other such things.”

Despite Björgólf’s search, there have been many examples of how high-ranking Samherji employees talk, either directly about bribes and the need to pay them, or indirectly with reference to high payments to high-ranking or well-connected Namibian associates, without explanations of what was paid for . Employees in Samherji’s accounting department were surprised by these payments and tried to get an explanation, but did not receive any.

The assistant with the email

The data in the Samherja case unequivocally indicate that Þorstein Má had trouble communicating via e-mail. Almost all of his communications with Samherji staff, both those closest to him and others, go through the email address of his assistant, Margrétar Ólafsdóttir. Emails sent from her email address are often signed by Þorstein.

During the aforementioned hearing, he gave her email address, asked for an email address for the police to contact him later.

Part of the district prosecutor’s investigation documents is Margrétar’s mailbox, which Samherji handed over at the office’s request. It shows that Margrét forwarded many of the computer messages to another email address, identified by Þorstein’s initials, but hosted outside the Samherja Complex. In Þorstein’s opinion, e-mail was not a means of communication that he thought of.

“Does everything need to be in post between people?” he asked his subordinates when ideas about horse mackerel fishing in South Africa were being discussed in 2017 and Stundin reported in 2021.

Þorstein’s subordinates knew this well. “Have you sent an SMS to ÞMB yet?” Jóhannes’ colleague asked in an email in 2014. “Tried sending him a line on Skype and also an SMS from your Namibian number to his German one.”

The third wheel

Þorstein’s text messages and photos found on Jóhannes’ computer indicate that the communication and relationship between Jóhannes and Þorstein was different than the CEO and company representatives have claimed. The text messages that passed between them for many years testify to that.

In Jóhannes’s possession were found quite a few photos taken of

them spending time together outside of work, in Iceland and abroad. As evidence of that, there are photos taken in the Esjugungän walk that Jóhannes went on together with Þorstein and his then-girlfriend, Kristina Edwald, in the middle of July in 2012. Of the photographs, for example, only the three of them were in the walk.

Six days later, on July 19, Jóhannes and Þorsteinn were back at Esjuna, but then with some other colleagues at Samherja.

Shortly before, or in May of the same year, Þorsteinn had gone to Namibia and visited Jóhannes, who was then busy working on the company’s progress together with Aðalstein Helgasyn. During the trip, Þorsteinn met Bernhard Esau, the then minister of fisheries in Namibia, in a secret meeting at the minister’s farm. A meeting described as a key meeting to seal a relationship, which is currently under the biggest corruption investigations, both in Namibia and Iceland.

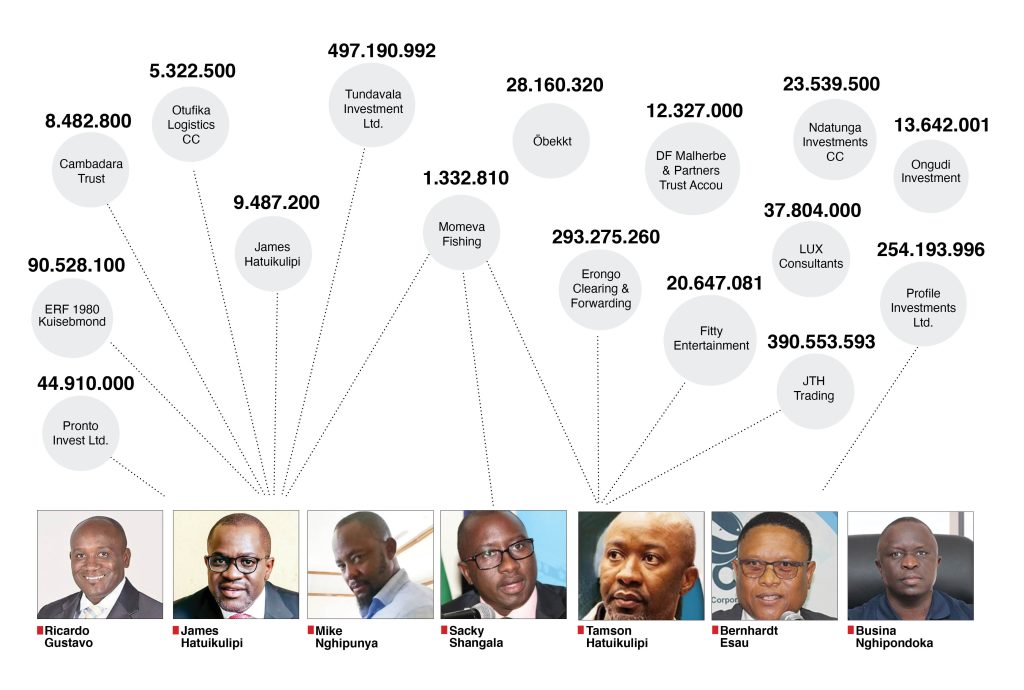

During interrogations, Þorsteinn has admitted to having met the Namibian Minister of Fisheries, as photographs confirm Þorsteinn’s presence at more than one such meeting, both at the farm and at the minister’s son-in-law’s home in October 2015. Like the minister, the son-in-law is in custody because of his dealings with Samherji.

The SMS stream from Þorstein to Jóhannes also does not match his description of his indifference in the south. “I never managed any of Samherji’s companies in Namibia and had limited knowledge of their day-to-day operations. Mr. Stefánsson managed the operations of Samherji in Namibia until he was removed,” said Þorsteinn in a statement to the Namibian government due to court cases in that country, which are aimed at those who accepted payments from Samherji.

According to the source’s information, the SMS messages have been brought to Þorstein Má in questioning. It was done recently. They will most likely be held during the last hearings before a decision is made on whether and who will go to trial in the case.

Didn’t know about this communication

Þorsteinn Már Baldvinsson said in an interview with Heimildina that he did not want to comment on the phone records or anything else related to the district prosecutor’s investigation into the alleged violations of the law by him and his subordinates, but repeated his earlier words: “I know nothing about Jóhannes.”

Björgólfur Jóhannsson, who was acting director of Samherji for a

while, and who appeared on behalf of the company after the Samherja documents came out, said in a conversation with Heimildin that he had never heard that there were phone messages between Þorstein and Jóhannes.

“No, not a word,” said Björgólfur, who said he did not know that phone data had been part of the investigation by the Norwegian law firm Wikborg Rein.

“No, I don’t know that. When you’re going through documents, you’re not going through some personal documents or phones and things like that.”

Björgólfi said it was a big surprise to hear about the number of SMS messages between Jóhannes and Þorstein Más. Like hearing that it was a message that went both ways.

“I knew that Jóhannes was said to be very good at sending mails and that they weren’t always answered, but I didn’t know about this. It’s also been a while since I’ve been in this, as you know.”

However, Jóhannes said that a large part of the communication was in a form other than e-mails, had taken place via phone or video calls, has this not caused you to have Wikborg Rein investigate it further?

“Like I said, I’m just not sure that this was looked at.”

But don’t you know it was done?

“No, I don’t do it,” said Björgólfur, who was appointed chairman of Samherja’s special compliance committee, in the company’s efforts to respond to the Namibia issue. However, he no longer sits on the committee.

“No, no, no. It’s been quite a while and it only lasted a short time. However, the committee is still active and has done a lot of work. After all, such committees are employed in most such larger companies.”

You are not working for Samherji?

“No, no. I haven’t done it since the turn of the year 21-22.”

What did the accountant know?

During the investigation of the Samherja case here in Iceland, nine current and former employees of Samherji have been given the legal status of a defendant, due to suspicion of bribery, money laundering and enrichment offences. In addition to Þorstein Más,

we can mention Ingvar Júlíusson, the financial director of Samherji’s foreign operations, and Aðalstein Helgason, who was in charge of the company’s African operations until he retired due to age in 2016. Both of them were involved in payments to drawer partners in Dubai and Namibia, which were used to deliver bribes to influential Namibian people.

More people connected to the company have been called as witnesses. Among them is Arnar Árnason, Samherji’s accountant for many years and co-owner of the audit giant KPMG. During a hearing in March last year, Arnar was presented with documents that KPMG handed over to the district prosecutor, all of which were related to his work on the audit of Samherja’s parent company.

Among the data was an overview of unexplained payments from the Namibian company Samherja in 2012. It deals with unexplained cash withdrawals and payments that have naturally raised questions. The answers to them should have set off a warning light.

For example, a cash withdrawal of up to ten million ISK marked “fishing license costs” for which no invoice was found. In the explanations, this is said: “Facilitation fee due to the trust quota.” Jóhannes is going to provide an account.” It says there that millions of ISK worth of banknotes were withdrawn from a bank in Namibia and used to pay an “agency fee” to an unnamed party due to the allocation of quotas to Samherji from a public fund in Namibia. Another cash withdrawal, half the amount, is also on the list of payments that need clarification, for the same reasons. The explanation is said: “Aðalsteinn agreed, Jóhannes needs to provide an account.” “

Another document submitted to the auditor and which may have been included in his working papers contains an overview of over ten entries in the books in Namibia. There, four transactions, worth a total of ISK 150 million, over a period of just over one year, marked only as consulting payments, attract obvious attention.

Yet another example that attracts attention is in a document submitted to the accountant of Samherji in Iceland, where you can find a breakdown of the so-called quota costs of Samherji in Namibia, payments for quota fees to the state and profit sharing, they are said to be included in the calculations, but also what is called ” Actual consulting costs” without further clarification.

The accountant’s records show that he had a lot of contact with managers in Namibia and one in Cyprus. For example, Arnar went to Namibia and had a meeting there, as well as going over the situation in relation to the settlement of the Samherja group in detail. At the same time, Samherji’s subsidiaries paid close to two billion ISK due to invoices for unclear consulting payments, up to 70 million ISK in one and the same transaction, to an unknown drawer company in Dubai.

KPMG auditor Arnar’s only comments regarding Samherji’s activities in Namibia are about the repeated lateness of Namibian colleagues. His audit reports do not show that during the entire time Samherji worked in Namibia, any comments or cautions were made regarding these exorbitant payments by the subsidiaries in Cyprus and Namibia.

The guidelines of KPMG, an international auditing firm, draw lines regarding the auditor’s obligations to be on the lookout for evidence of bribery or corruption. It is specifically pointed out that three-quarters of all the largest bribery cases in recent years are characterized by the fact that bribes were paid through intermediaries, in the form of consulting payments.

In particular, it is warned that auditors need to be especially alert to the risk of bribery, when it comes to activities in countries where the risk of corruption is considered higher than most, and that the risk is especially high when the business is in some way related to government representatives, employees or public sector institutions.

“Does the subject have an international footprint and does it operate in countries where corruption is common?” Does the subject work in an industry where contact with public officials is extensive? Does the subject use a significant number of third parties to manage its sales or operations in other countries?

Judgments can be sought abroad where similar payments have been discussed. KPMG in the UK was fined the equivalent of 650 million ISK in 2022 for not fulfilling its obligations and reporting clear signs of abnormal business practices, when Rolls Royce paid bribes to gain valuable business relationships in India in 2010.

The auditor KPMG, who himself was fined the equivalent of tens of millions of Icelandic ISK, was said to have overlooked obvious signs of abnormal business practices due to two payments, worth ISK 800 million, that Rolls Royce paid to an Indian intermediary in order to enter into valuable business with the Indian government.

Rolls Royce had been fined close to 40 billion ISK for numerous bribery offences.

The auditor’s carelessness was said to be particularly serious given that at the time of the audit, there was a large and loud discussion about the risk of bribery in the same sector, as well as the fact that intermediary payments were the most common form of bribery.

KPMG in Iceland and Samherji announced shortly after the Samherja Documents came to light at the end of 2019 that their business relationship was terminated and another company would be in charge of the audit of Samherja Holding, which at the time was responsible for all of Samherji’s foreign operations.

No explanation was given for this, representatives of Samherji and KPMG refused to answer what the reason was.

The source spoke with Hlyn Sigurðsson, the managing director of KPMG, over a year ago, and in that conversation he said that he did not want to discuss the termination of the business relationship at the end of 2019. When asked what the responsibility and role of the KPMG auditor was, they would suspect something abnormal or illegal in their work. and whether they had an obligation to report it to the authorities, Hlynur said: “It is not our job to do that.” Our responsibilities are primarily to the board and shareholders. If something illegal is seen, it is our duty to report it to the board and shareholders. Our responsibilities are primarily to them.”

Leave 0

In addition to auditing the accounts of the members of the group, Arnar seems to have been brought in to scrutinize and scrutinize the transfer of ownership of the entire Namibian company from the UK.

In a document that appears to have been in the files for KPMG’s audit of Samherja companies in 2015, it is discussed in some detail how Samherja companies in Namibia are going behind their Namibian co-owners in business and talk about the need to keep it secret. At the same time, this document specifically deals with Samherji’s two million ISK annual “consulting payments” to his “son-in-law” for going quarterly and looking after the fish shops that Samherji established there, at the request of the locals.

However, Samherji had to continue paying these same consultancy payments for three years, after the fish shop was closed.

In the accountant’s notes, it also says that Ingvar Júlíusson, the financial manager of Samherji’s foreign operations, was requesting that the “definition of related parties be reduced” as it would be “politically sensitive” if it was revealed that Samherji had full control over its shipping company Katla in Namibia, although it was made to appear that the company was majority owned by Namibians, which was a condition for being allocated a quota in Namibia.

There is also a detailed overview map of Samherji’s complex operations and how the Namibian operations go from being owned by a British Samherji company to being owned by an offshore Samherji company in Mauritius. The transfer of ownership and no less the fact that the income generated in Mauritius was not declared, were one of the big reasons why Samherji had to correct his tax returns in Iceland and pay hundreds of millions of ISK in taxes and fines.

One of these documents is the minutes of the meeting of the auditors of the Samherji companies in Namibia, at the beginning of 2015. It specifically discusses the influence of the drawer company Mermaria Invest, which Samherji founded in Mauritius, in order to bring profits out of the country in Namibia and on to Europe, without pay tax on it.

The Mauritius company is said in the auditor’s notes to change the fact that one of Samherji’s subsidiaries in Namibia will subsequently be run at zero and only what is necessary will be kept in the company.

“[W]hen this is brought in, the result will be 0+ what will be

considered a necessity.” to leave inside the fé[la]” reads the accountant’s handwritten points.

Accountant Arnar Árnason did not want to comment to the Source.

Available for Samherji

Previously, the draft of KPMG’s report on so-called “transfer pricing” has been discussed, where it was examined how decisions were made in Samherji’s corporate network. By law, transactions between related companies must be conducted on the same terms as with non-related companies. It was another KPMG employee who prepared that report, but in his e-mail communication with Örna Bryndís Baldvins McClure, Samherja’s lawyer, and Ingvar Júlíusson, CFO, it is stated that he changed the report based on the company’s comments.

“I received the information from my superiors that in a meeting with Þorstein [Má Baldvinsson] last week, you expressed dissatisfaction with certain aspects of the work that KPMG has carried out,” said in an email from the employee, who worked at the tax and legal department of KPMG. “I hope that the updated reports will show that we want to do our best to do this work according to your wishes and requirements.” As I said at our meeting, these are your reports and we will adapt them to the comments you have and then we will also ensure that they meet the requirements of the transfer pricing rules.”

The draft of the report, which Þorsteinn and his employees were unhappy with, stated that all major decisions required approval and were usually initiated by the CEO. It was not allowed to be written like that in the report, and KPMG employees were invited and had already changed the wording. “The employees of the group must say whether this requires the CEO’s approval in all cases, or whether it may be right to say in some cases that the matter needs to be discussed with the CEO,” said an anonymous comment made in the document.