4 August 2024

… Walvis Bay, Lüderitz, or Oranjemund?

Namibia is currently hot property in the oil and gas exploration industry.

For an industry that is supposed to be in decline due to the world’s decarbonisation goals for 2050, it is showing remarkable resilience and strength.

What is now known is that there is an expected 11 billion barrels of oil and 9 trillion cubic feet of gas at the mouth of the Orange River.

The Orange River has been remarkably kind to Namibia, providing it with diamonds for the last 70 years, and now oil.

Those in the industry believe there will be at least five or six years more of exploration before actual drilling and exports begin.

This is expected to be only the beginning of further discoveries, and oil majors as well as the smaller explorers are falling over themselves to obtain exploration licences – both on and offshore.

‘SUPERGIANT’

The discoveries are in an area approximately 290km from Oranjemund, with three companies, TotalEnergies, Shell and the Portuguese firm Galp having recently announced major discoveries.

In the oil industry, a major discovery of more than 500 million barrels is called an ‘elephant’.

Anything over 10 billion barrels is termed ‘supergiant’.

This is why interest is growing rapidly among oil companies in further exploration in the Orange Basin and further north in the Lüderitz and Walvis Bay basins.

Chevron also has licences in the same area, but has not yet announced major discoveries.

To keep this in perspective, if the estimated reserves are proven then from what is known now, the Orange Basin contains roughly a quarter of the 46 billion barrels of oil that has been extracted by the United Kingdom from the North Sea since the mid-1970s.

There is every reason to believe that given the excitement and level of exploration, more oil will be found in the coming five years of exploration.

The Orange Basin is set to make Namibia the third-largest oil producer in Africa after Nigeria and Angola.

THE NEXT ABERDEEN?

Aberdeen in Scotland has become the base for the oil industry in the North Sea.

It has grown substantially and prospered as many spin-off industries have emerged.

The immediate question arises as to which of Namibia’s three coastal towns, Walvis Bay (with a population in 2023 of 103 000), Lüderitz (with a population of 16 125 ) or Oranjemund (with a population of 7 440) will become the Aberdeen of Namibia?

This will determine the direction of investment in years to come.

Each town has advantages and disadvantages for the oil and gas industry, and each town will be competing for a share of the industry spin-offs, including that which will occur when hundreds of very well-paid oil workers will come or temporarily stop on a weekly basis.

Walvis Bay and Lüderitz have much in common with what Aberdeen was before North Sea oil totally transformed the city.

Both Lüderitz and Walvis Bay are essentially fishing and port towns, like Aberdeen was in the early 1960s.

Lüderitz is stuck with scores of South African Manganese trucks that barrel through the centre of town to the port.

Walvis Bay is the centre of the horse mackerel industry, while Lüderitz is still dominated by the Spanish/Namibian hake industry.

Walvis is also the centre of the export of granite, which is sold to China at rock-bottom prices.

The port has long been the key point of export for copper, salt, fish, and basic raw materials coming out of Namibia.

The Portuguese state-owned oil company Galp is said to be basing its operations around Walvis Bay because it needs the port and dry dock facilities that are only found there.

Those who are working in the supply industry state that Shell has yet to make a decision and is considering Walvis Bay and Oranjemund.

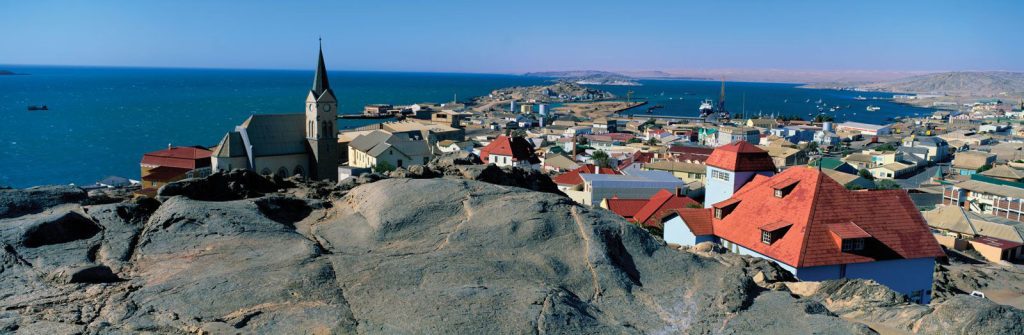

LüDERITZ

Total, it appears, has unofficially chosen Lüderitz as the centre of its operations.

Those closely associated with Total are renovating the hotel, as well as other buildings which will be used.

It should be noted that all these oil companies do not normally buy residential properties, and this is done through intermediaries who provide them as rentals to staff of the oil company.

Lüderitz is a charming colonial historical town with real tourism potential if the city can deal with its land shortage.

It is is boxed in by the Sperrgebeit and surrounding hills. The town has over 80 listed buildings that cannot be changed because of their historical importance.

The old Kapps Hotel is being renovated and its German-era façade preserved.

It will be accommodation for what city officials confirm would be TotalEnergies employees.

Lüderitz mayor Phil Balhao says: “There is no land around Lüderitz, and the town is acutely aware of the problem, so it is trying to deal with its land shortage issue by developing two satellite towns 25km and 50km from Lüderitz on the road to Aus.”

ORANJEMUND

Oranjemund has the feel of a small English town designed and built in the inter-war years.

It still has a number of oryx grazing on its green urban lawns.

The town has an almost-unNamibian feel to it because of its relative lack of informal settlements.

It is a town made of diamonds from diamonds, but so was Elizabeth Bay.

Namibians who have been raised there speak of it in almost mystical terms as the ideal place to be raised.

De Beers has kept the town closed until 2017.

It was not possible to enter without a permit, and so one finds the anomaly of a diamond-mining town which has no official or unofficial red-light district.

THE SEX WORK ISSUE

Unless Oranjemund and Lüderitz are able to provide the sources of entertainment young men who are making a bucket of money and have been working 12 hour shifts for three weeks in the middle of the South Atlantic would want, they would likely become little more than a convenient transit point to Cape Town’s brothels and drug dens.

Even Walvis Bay and nearby Swakopmund, with its less than salubrious quarters, would not attract well-paid oil workers.

The fact is that once the oil workers and their money arrive in any of these towns, the sex workers would migrate to the

coast.

It is for this reason that the Namibian government needs to carefully plan and work towards an almost immediate commitment to Namibianisation and gender balance of the oil-rig workforce, which would otherwise be dominated by foreign workers if nothing is done now to train Namibians.

This requires starting to plan and coordinate with Shell, Total and Galp now so that the oil industry becomes a source of growth and benefits to working Namibians and not just for the elite.