After several months of investigation and travelling the treacherous routes used by human traffickers, a chilling underworld of exploitation is exposed. The inquiry pulls back the curtain on a network that preys on vulnerable migrants, unveiling the powerful figures pulling the strings, their corrupt grip on the Malawi government, and entrenched corruption within its security forces. The result is a ruthless but lucrative business that leaves a trail of death and despair.

By Golden Matonga, Jack Mcbrams and Julius Mbewe | 8 March 2025

An Ethiopian human smuggling syndicate has embedded itself deep within Malawi’s government, creating a vast network of enablers that facilitate a brutal and dangerous journey for desperate migrants seeking to escape war and poverty in Ethiopia in search of a better life in other countries, including South Africa.

The investigation reveals that this human trafficking system primarily operated out of the Dzaleka Refugee Camp in Malawi. Gang leaders profiting from and running this trafficking operation have not only co-opted senior government officials, including police and immigration officers, to help ensure the migrants’ passage, but certain cabinet ministers also turn a blind eye and intervene when necessary in return for lucrative protection money. As a result, this deadly trade is thriving. These gangs not only operate, profit, and launder the proceeds of this crime with impunity, but they also enjoy high-level support to ensure there is no competition from rival operators. Numerous official attempts to dismantle this gang have failed.

The gang members behind the human trafficking syndicate are wealthy. They own luxury hotels, mansions in Malawi’s most affluent suburbs, and nightclubs even within the poverty-stricken Dzaleka Refugee Camp, which is home to some 53,000 refugees, primarily from the war-ravaged Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes region.

The PIJ’s investigation, which involved over 30 sources from Malawi’s state security apparatus, other government departments, civil society, and communities in Dzaleka, confirms how these gangs operate with impunity. The investigation highlights the systematic corruption of Malawian officials, including marriages to relatives of senior military and police officers. PIJ reviewed intelligence files, police dossiers, court documents (including those related to gang leaders under secret military detention or previously deported), and exclusive images and footage of safehouses within Dzaleka, where trafficked migrants are sheltered before being smuggled through Mozambique to South Africa—primarily via the Dedza border.

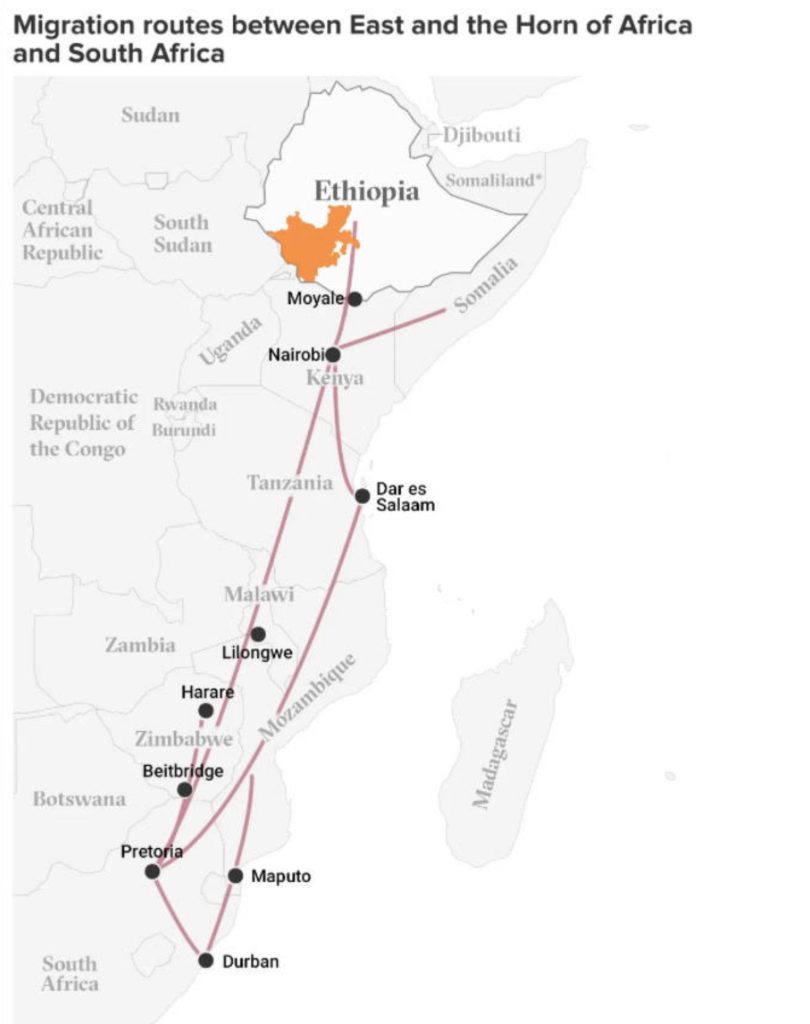

A bloody route

How Malawi is used as a conduit by gangs to smuggle mostly young Ethiopian migrants destined for South Africa has been public knowledge since April 2022, when a mass grave was discovered containing 30 Ethiopian bodies in the Chikangawa Forest in northern Malawi.

The national outrage prompted a high-profile murder trial involving the stepson of former president Tadikila Mutharika, whose cargo van was allegedly used by the traffickers.

Mutharika was acquitted, but the trial gave the public its first glimpse into the high-level protection afforded to gangs that trade in humans, some as young as 13, who may not survive the perilous journey.

The migrants are smuggled primarily from the Hosaena region of Ethiopia, traveling south through Kenya and Tanzania before finally reaching Dzaleka Refugee Camp in Dowa, entering through Malawi’s northern border with Tanzania.

To evade detection from law enforcement, traffickers force migrants to travel at night, sleep in forests, cross near-flooding rivers, or sail on Lake Malawi in unsafe boats. Some migrants succumb to illness and exhaustion. The weak or sick are discarded, left to die, or murdered. This was starkly revealed in 2012 when mass graves of migrants were discovered and when a boat capsized on Lake Malawi, claiming 47 lives. For migrants, life is disposable. In 2021, autopsies of 30 suspected Ethiopian migrants found in a mass grave in Chikangawa Forest Reserve revealed that some were murdered.

PIJ’s investigation traced traffickers’ routes, exposing porous borders and corrupt and negligent authorities that allow the gangs to operate with ease and impunity.

One key border crossing point from Tanzania into Malawi is Katininda on the Songwe River, less than 2 km from the Songwe border port. During the day, businesspeople also use this crossing point to dodge paying border taxes for goods. While motorcycle taxis on either side of the border transport goods in broad daylight, humans are transported across the Songwe River on canoes operated by locals.

Despite occasional raids by the Malawi Revenue Authority (MRA) and police, the illegal trade thrives. As a community member there told PIJ: “The locals are very violent and threaten anyone who dares disrupt their business.”

At night, the Songwe border crossing is where migrant smugglers from Tanzania hand the migrants over to Malawi-based gangs. Once canoed into Malawi, the migrants are sheltered either in a safehouse or hidden in the nearby Ngana Mountain Forest while the smugglers plan a route to Dzaleka Refugee Camp in central Malawi.

“Sometimes they ask the communities to house them [smuggled migrants]. They can pay as much as K100,000 (US $58) per night,” a member of the border community told PIJ.

From the Songwe border, they are driven to Karonga Boma via Toyota Sientas, a popular commuter mode of transport in the area, or cargo vans, a more secure but expensive option. Those running this early stage of the operation are local businesspeople, including informal foreign currency traders known locally as “achenji.”

Before reaching the Boma and eventually Dzaleka Refugee Camp, they must navigate numerous hurdles in the form of police and military checkpoints. Often, a sweeper car is in front of the vehicle transporting the migrants. The sweeper car bribes police officers at various checkpoints and contacts senior officers when facing resistance.

The enablers

A key security source told PIJ that the trafficking syndicate is allegedly led by figures such as Ernest Phambala, a well-known politician who was previously a member of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) but recently joined the ruling Malawi Congress Party (MCP).

A senior UN official—speaking to PIJ on the condition of anonymity as they were not authorized to comment—described the gangs as extremely dangerous.

“Even I am scared of them,” a UN official told PIJ. “I have heard gruesome stories of people disappearing after being thrown into drums of acid. Nobody has ever heard of them again.”

In November last year, police were shocked to find the bodies of three Ethiopians inside the Chiweta mountains when they went to recover a truck belonging to Gaffar Transport, which had fallen over a cliff.

“They found bullet wounds and stabbed bodies,” said a source familiar with a police report on the incident.

PIJ has uncovered evidence of how gangs beat up refugees inside the Dzaleka Refugee Camp if they are suspected of collaborating with law enforcement to dismantle the gangs. Despite police recording statements in the case, no one has been arrested to date.

In October, a seven-man police team in Ntchisi district was asked to transport five Ethiopian migrants who had completed a jail sentence at a local prison to Dzaleka Refugee Camp for processing with agencies handling asylum seekers and refugees. The police officers involved in the incident claimed the official police vehicle had no fuel. A leader of the Ethiopian community, identified as Shigege, who came to oversee the process, offered to pay for the fuel. He transferred K250,000 to Donald Holla, 56, the police administrator.

While en route, according to those familiar with Holla’s version of the story, he claims he was invited into Shigege’s car and given K50,000. However, he later received a call from Nyirenda, his superior at the district, instructing him to get out of the car and return to the office with the migrants, as Shigege was planning to ambush them.

As they changed course, an officer who accompanied Holla claimed that a vehicle reportedly with officers from Regional Police headquarters approached them and requested the officers hand over the migrants to the supposed regional headquarters team.

Surprisingly, the supposed regional headquarters team included Ephant Ngonamo, a police officer from Kasungu district who had previously been stationed at Dowa police station, which oversaw the Dzaleka refugee camp for 10 years.

“They mentioned the name of a very senior officer who had issued the orders,” said one officer who spoke to PIJ.

“Those migrants never reached Dzaleka. They are nowhere to be seen!” he exclaimed.

Holla, who declined to comment when contacted by PIJ, was later placed under arrest along with Ngonamo and Virginia Kasiya, a police prosecutor. They were charged with conspiracy and abuse of power, but both charges were dropped, and he was charged with a minor office abuse misdemeanor.

National Police spokesperson Peter Kalaya confirmed Holla’s arrest to PIJ but reserved further comment as the matter is now in court.

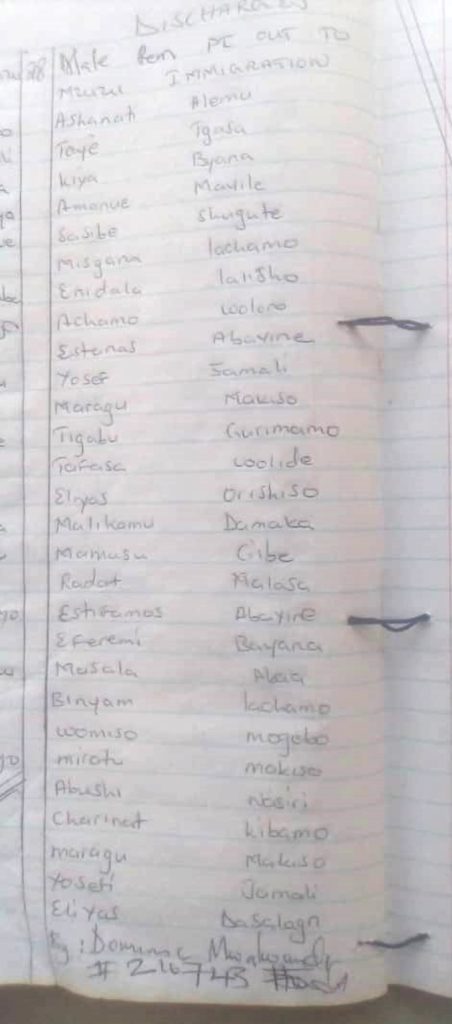

Concerns have also emerged regarding Malawi’s Immigration Department amid suspicions that some officers are aiding human smuggling, even working with smugglers to “strategically” arrest and deport migrants, ensuring they are trafficked again.

In July 2024, the High Court in Mzuzu ordered the release of 300 migrants imprisoned at Mzuzu Prison. In response, the UN agency, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), offered financial support to the Malawi Government to prepare for the deportation, including purchasing air tickets. However, the Immigration Department did not include 30 migrants in the deportation plan, citing technical challenges such as verifying their identities.

Later, instead of asking IOM to support their deportation, the department bused the 30 migrants and dumped them at the Songwe border in Karonga, without handing them over to the Tanzanian government. According to Edward Kuntuseya, Programs Manager for Mzuzu-based NGO Youth Watch Society, which tracks smuggling, some of the migrants deported that day would later be arrested by the Malawi Defence Force when it conducted a raid at the Dzaleka Refugee Camp and are now at Maula Prison, serving another sentence for illegal entry into Malawi.

The name of the immigration officer responsible for collecting the migrants, Dominic Mwalwanda, can be seen on the release documents from the prison.

“When Ethiopian undocumented migrants are released from Malawi prisons, they are often ‘deported’ to Dzaleka, into the hands of traffickers, instead of being sent back to their home country, unless the deportation is done by air,” Innocent Magambi, INUA Advocacy Executive Director, told PIJ.

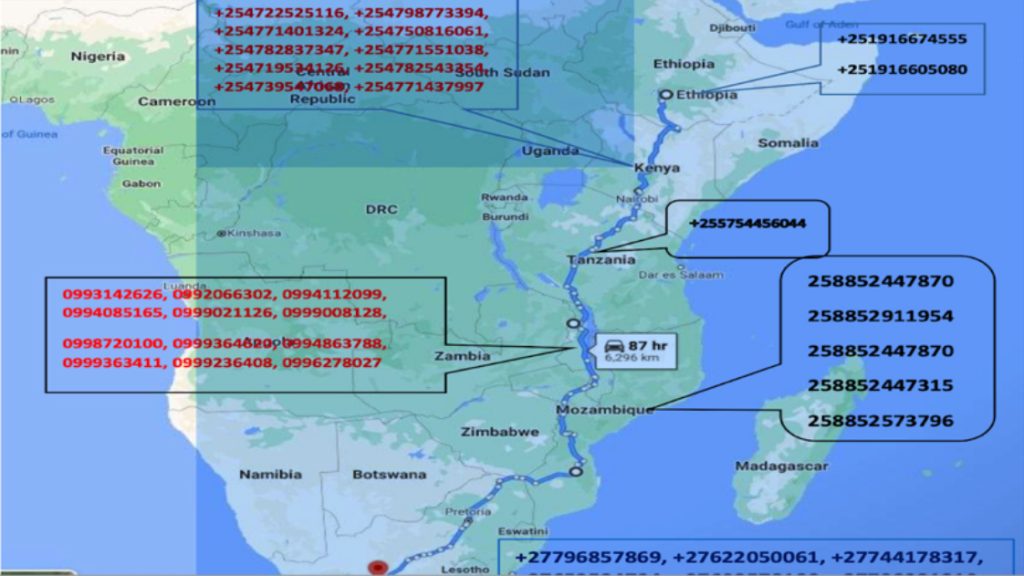

PIJ has a dossier from the Police Crimes Intelligence Unit detailing a 2020 investigation into human trafficking syndicates. It confirms that police are involved. There is evidence in this dossier of police receiving money from traffickers, proof of communication between them, and even evidence of police assisting migrants to get to other countries under the pretense that they were being repatriated.

Some police officers from Mzuzu City, northern Malawi, were arrested as a result of this investigation, which also targeted the activities of one immigration officer at Songwe Border whose Airtel Money account is registered as Tabia Mwakawanga. His number made 496 communications with a number belonging to Mobin Mohammed, a suspected trafficker. The immigration officer’s number also made 15 calls to a man known as Duke, a suspected Malawian trafficker.

The Kingpins

Two names keep appearing in the 2020 investigation: Ardnaw (also spelled Aldno or Adnaw) and Brano—both Ethiopians who later acquired Malawian citizenship. They are allegedly the kingpins of this illegal trade, owning a combined total of 12 safe smuggling ‘prisons’ or safe houses in Dzaleka. They are described as rich and powerful.

“They now live in mansions and drive posh cars; not even cabinet ministers would dream of driving such luxurious cars,” said one source.

Ardnaw, who used to own a nightclub by the same name in the refugee camp, works with a man known as Ibrahim. Brano has two brothers, Mukalni and Barakat. He works with them and a man named Buzayo.

Ardnaw recently sold his flashy nightclub inside the Dzaleka Refugee Camp, where the Ethiopian community is regarded as affluent. He is reportedly on the run, but his club still bears his name.

Poverty-stricken refugees in the camp openly speculate about the source of wealth for men like Ardnaw, being Katundu(goods) or makatoni (cartons)—the derogatory code name for smuggled migrants.

“The bar is just a front for that business. Everybody here knows people are just afraid of them,” a close associate of Ardnaw told our undercover reporters.

Between 100 and 300 smuggled Ethiopians reportedly pass through the camp weekly, with traffickers demanding between US $5,000 and $7,000 from the relatives of each trafficked person, according to INUA Advocacy, a non-profit organization advocating for the rights of refugees.

INUA Advocacy estimates that 95 percent of all Ethiopian nationals registered as either asylum seekers or refugees in Malawi are involved in trafficking and smuggling, with officials in the Ministry of Homeland Security either fully aware of or benefiting financially from the gangs’ activities.

The 2020 Police Crime Intelligence Unit report also identifies Bashew as a key trafficker and Aubrey Duke as a key figure in the trade, receiving money from the leading traffickers to facilitate the business in Malawi. (Police arrested Duke following the discovery of the 2022 mass grave in Chikangawa before being acquitted by the High Court.)

“Getachu Akililu and Adno Bashew are currently the main traffickers. It has been established that they are the ones receiving international calls. They have their men who link with Aubrey Duke,” reads the report.

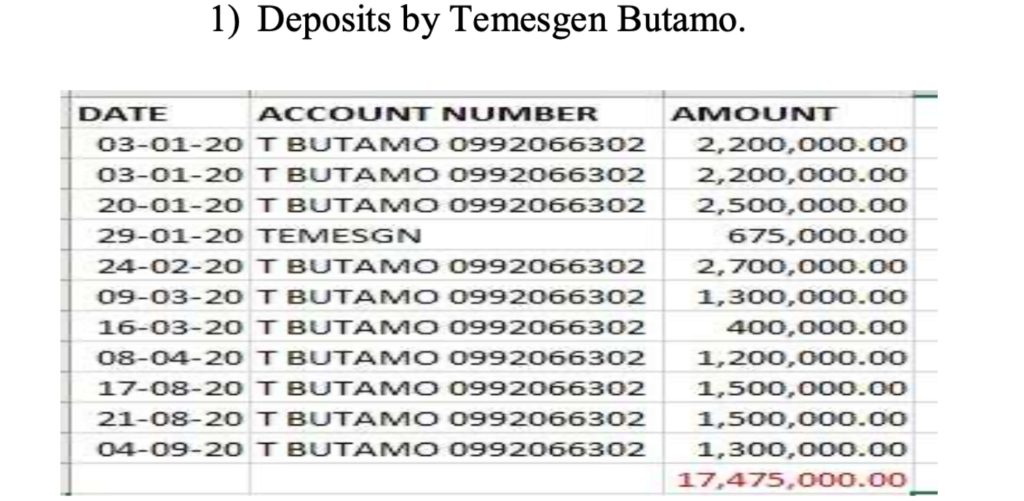

The report says Aubrey Duke owned a Premium Account with FDH Bank based in Karonga at some point and was credited with a total sum of K115,291,590.08, equivalent to USD 152,126.91 at the time of the investigation. Analysis of the deposits into the account showed that money was being deposited by several suspected traffickers, including Abramo Abo, Temsmen Butamo, Muhammed, and Samson Mulugeta. All the deposits were withdrawn the same day they were deposited.

The report recommended that Getachu Akililu (Gecho), Adno Bashew, and Ernest Phambala be questioned for their involvement in human trafficking.

War on Gangs

In July 2024, INUA wrote to Malawi’s President Lazarus Chakwera to report on the syndicate’s activities and the role of government officers in aiding and abetting these criminal activities.

On 12 October, three months after Magambi’s letter, the military raided the Dzaleka Refugee Camp for the second time, following an earlier raid in July. Witnesses described a violent, gunfire-filled operation.

Most sources, including lawyers, agree that almost everyone arrested that day was allegedly involved in the human trafficking syndicate.

“I cannot tell you here that my client is clean,” one lawyer told PIJ.

“I just don’t believe in the manner the MDF [Malawi Defence Force] is executing the matter. It’s like they are above the law,” he said.

According to some accounts, eight Ethiopians arrested during the second MDF raid on Dzaleka Refugee Camp in October remain in secret military detention.

“They have neither been deported nor taken to court,” said a human rights activist speaking on condition of anonymity.

Various sources named those in detention as Isaac Mitiko, Gecho, his brother Subside, Muhamad Ahmed, and Samson Belachew Mulugeta, a rich businessman who owns a sprawling hotel in Lilongwe’s affluent Area 6 neighborhood.

“He was doing small businesses, and he established his toilet tissue manufacturing business later on at Njewa,” recalled a long-time friend from the refugee community.

“He was very present on the social scene. We could interact at Ethiopian Day celebrations and meet for a few drinks. Then we started hearing whispers; allegations that Samson was involved in the human trafficking business. Then we saw that he built the hotel,” said the source.

Mulugeta was reportedly arrested while trying to advocate for his relative, Muhammed Ahmed. Muhammed, according to several sources, was accused by the military of being part of the Dzaleka-based Ethiopian traffickers.

PIJ can confirm that Mulugeta was part of the trafficking syndicate, and his name appears on the list of people depositing money into Duke’s account. However, the state has not charged him with any crime. Following his arrest last year, he was deported. This, however, did not deter him.

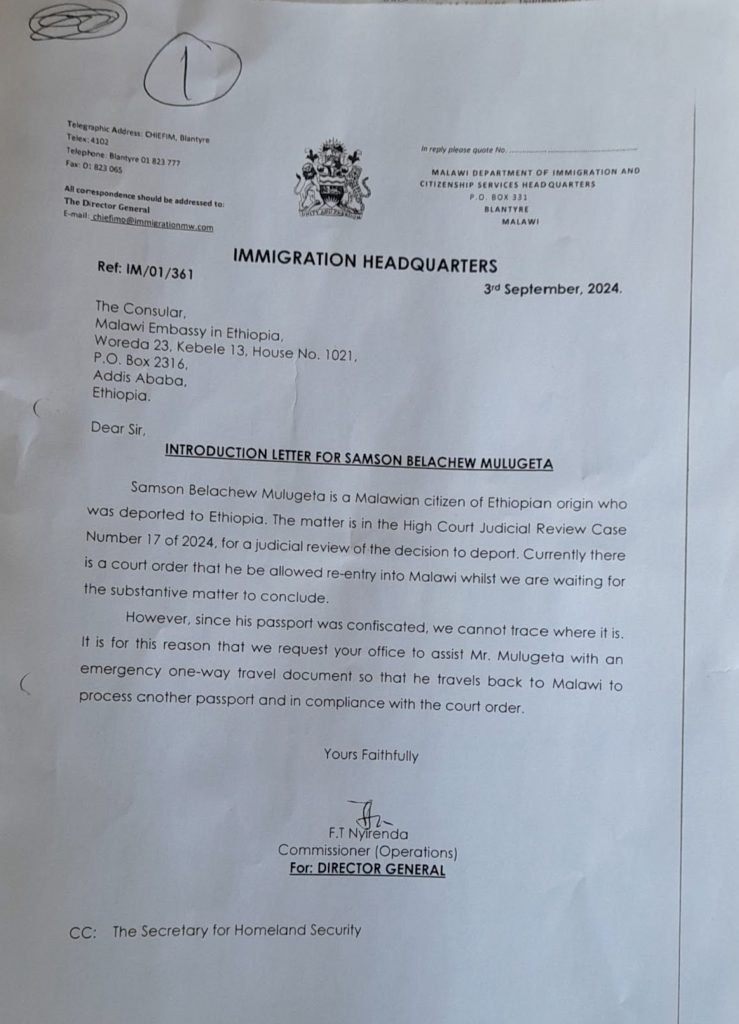

He engaged a top lawyer and former Attorney General, Kalekeni Kaphale, which led to a court order (case number 17 of 2024) for the Immigration Department to allow Mulugeta back in the country pending a hearing of his case.

But Mulugeta’s plan to return was not without hurdles. He was arrested on his return by the Immigration Department, which also confiscated his passport. The Immigration Department was led by Brigadier Kalumo, a reputed no-nonsense former military officer.

PIJ has learned that Mulugeta’s passport went missing.

The Immigration Department was forced to issue Mulugeta a one-way travel document to allow him to travel from Ethiopia back to Malawi. Among documents sourced by PIJ is a letter from the Immigration Department, authored by Commissioner for Operations Fletcher Simwaka, asking the Malawi Consulate in Ethiopia to issue the travel document.

“Currently, there is a court order that he be allowed re-entry into Malawi whilst we are waiting for the substantive matter to conclude. However, since his passport was confiscated, we cannot trace where it is. It is for this reason that we request your office to assist Mr. Mulugeta with an emergency one-way travel document so that he travels back to Malawi to process another passport and comply with the court order,” Simwaka wrote in a letter dated 3 September 2024.

However, what is unclear is whether Immigration consulted, or even informed, the police or the MDF about the move, or whether the move was sanctioned by the entire Immigration Department or just a rogue officer.

Interestingly, Mulugeta’s Facebook friends list is replete with officers from the Immigration Department, including a former Director General.

Does Mulugeta socialize with the officers, and are the relationships purely social? Or coincidental?

Whatever the case, what happened next when Mulugeta touched down in Malawi was the stuff that would turn Hollywood scriptwriters green with envy:

As soon as Mulugeta disembarked from the plane at Kamuzu International Airport, police and Immigration officers pounced on him. Kaphale, the super-lawyer, rushed to the airport—brandishing the court orders. He got him immediately released.

But the military arrived and bundled him into a vehicle. He has not been seen since, despite several court orders ordering his release or to be brought to court.

“The actions of the military suggest the military has suspended the Constitution. Is there martial law? Has the rule of law been suspended in this country?” Kaphale asked in an interview with PIJ.

Many supporters of the military’s actions say the military is the only institution willing and able to disrupt the activities of the smuggling gangs. After the two raids by MDF, for example, Brano and Adino, the leaders of the Ethiopian gangs, allegedly asked the Ethiopian community inside the Dzaleka Camp to contribute money to pay off officials.

But critics point to apparent rights abuses and constitutional violations, warning of the dangers of allowing the military to operate above the law. Others claim that the military, too, is corrupt, only arresting gangs that have not paid it off.

“They are running an extortion campaign,” said one lawyer. “If you are arrested, you have to pay them off to get released.”

One of the whistleblowers alleged that three vehicles belonging to detained or deported smugglers are now confiscated by senior military leaders.

The identity of the cars is as follows: a White Toyota Fortuner (NN 1644) belonging to Muhammed Ahmed, a Toyota Fortuner owned by Samy, an Ethiopian, and a Toyota X-Tray owned by Lire, a former trafficker now deported.

In a written statement responding to PIJ’s request, the MDF declined to provide information requested under the Access to Information (ATI) law, citing national security concerns.

“It is true that the MDF, in accordance with its mandate derived from Section 160(1) of the Republican Constitution, has been conducting operations at Dzaleka Refugee Camp to combat severe criminal activities and protect vulnerable individuals from exploitation.

“However, this matter pertains to national security. We regret to inform you that we may not be able to address all your inquiries. This decision aligns with the imperative to safeguard information crucial to national security, as stipulated under Section 30 of the ATI Act. Revealing such information would jeopardize the defense of Malawi under Section 30(a) of the Act and pose significant risks to the legitimate interests of the Republic of Malawi in crime prevention under Section 30(c) of the ATI Act,” wrote Major General S. M. Kalisha.

When PIJ returned to the mass grave site in Chikangawa Forest for this investigation last year, journalists uncovered another story that, were it not corroborated by several eyewitnesses, would be scarcely believable.

Three guards were on patrol inside the forest early in the morning when two Sientas approached them.

“If you find afisi (hyenas) in the forest, please let us know. They belong to us,” one of the guards told PIJ.

“They promised us 1 million each if we brought them the hyenas,” recalled one of the guards.

“They said, ‘If sons of presidents are involved in this business, why should you refuse 1 million kwacha?’”

The guards began the search and then called the police to help track the traffickers. Together with the police, they searched everywhere but found nothing.

Police officers at Chikangawa Police Station were involved in the matter.

Even in a place where a mass grave exists as a reminder of the dangers of smuggling, traffickers continue to operate.

“It’s difficult to stop this. We have very senior people involved. We once faced a situation when we found a convoy of smugglers. But the sweeper was a car branded in UTM colors. How could we do anything? The lead vehicle was being driven by a senior politician in the ruling party himself.”

The gangs continue to thrive.

- The Platform for Investigative Journalism (PIJ), a non-profit and independent news organisation dedicated to championing public interest journalism, produced this report in collaboration with Youth and Society (YAS) and INUA Consulting.