By Timo Shihepo and Roman Grynberg

18 June 2024

Namibia’s dream of becoming a green hydrogen leader faces a harsh reality check. A recent Oxford University study throws cold water on the project’s profitability, raising concerns about its long-term viability.

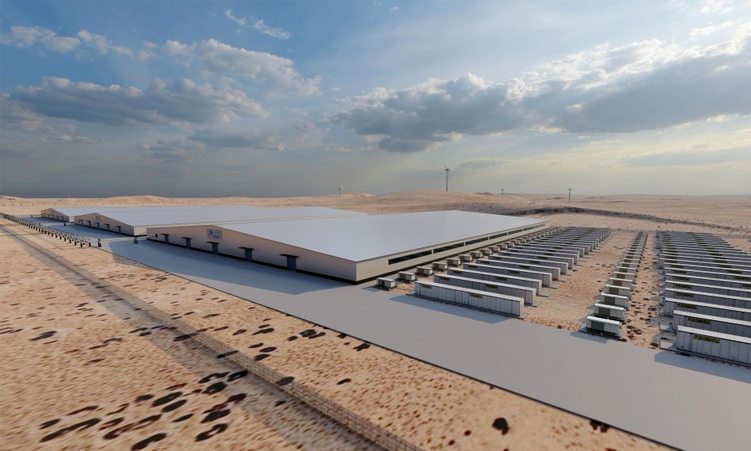

The March report by five Oxford engineers modelled production costs at the Hyphen Hydrogen Energy project at Lüderitz.

Their findings paint a gloomy picture, suggesting a levelised cost of hydrogen (LCOH) between €5,43 (N$101,52) and €9,21 (N$172,18) per kilogramme.

These production costs, coupled with ballooning development expenses – now projected to rise from over N$100 billion to N$220 billion – create a significant hurdle for the project’s profitability.

Adding to the pressure, north African and Middle East competitors with green hydrogen ambitions hold a geographical advantage.

Their proximity to Europe, the intended market, could undercut Namibia’s competitiveness.

The findings by Oxford University highlight the need for Namibia to address cost concerns and develop strategies to compete in the emerging green hydrogen market.

Other studies from institutions such as the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimate that green hydrogen production costs could be N$48 for Namibia by 2030.

The Namibia Investment Promotion and Development Board suggests that the price could be as low as N$27 by 2030.

The Oxford report states that “this points to the larger problem of opaqueness/darkness in current hydrogen modelling”.

While these price figures initially raised eyebrows, Hyphen Hydrogen Energy chief executive Marco Raffinetti last month told The Namibian there is a difference between an academic study and an actual project.

“It should be noted that this (the Oxford study) is a high-level study, using high-level assumptions,” Raffinetti said.

“The study is useful in confirming the competitiveness of Hyphen’s project site. However, there are significant differences between the academic set-up and the real-life project we are developing,” he said.

One of the critical differences highlighted by Raffinetti is the project’s reliance on both solar and wind generation to ensure a steady electricity supply to the electrolyzers.

Additionally, Raffinetti said the Oxford engineers’ conservative approach to the cost of equipment does not fully capture anticipated cost reductions over time.

“What is clear from Hyphen’s internal analysis, is that . . . Hyphen’s project location is believed to be among the three lowest-cost production locations,” he said.

Raffinetti believes Hyphen will be one of the only 10-GW scale projects globally in production by 2030.

“For a time it will be a seller’s market, and therefore regardless of Hyphen’s levelised cost of hydrogen, we are confident that the market price would be substantially higher and therefore the project will be viable.”

He said the company has not attempted to reconstruct the results of the Oxford University report.

Meanwhile, Namibia’s green hydrogen programme has been progressing with N$420 million having already been spent.

Hyphen is yet to complete its feasibility study.

PUTTING THE CART BEFORE THE HORSE

Normal due diligence requires a completed feasibility study before commiting to an investment.

But without even completing a feasibility study, the government has already committed to pump N$496 million into the Hyphen project to acquire a 24% stake.

Nikol Hearn, the head of Namibia’s Green Hydrogen Programme, last month defended the government’s decision to agree to be part of a project without a feasibility study.

“Regarding the commitment to acquiring a 24% stake before feasibility is done, it was part of the negotiations. The government has a 10% stake in oil blocks before they reach the final investment decision as well. This provides optionality and is a free carry,” she said.

Hearn said the government gets the option to invest in Hyphen, and through economic diplomacy, “we mobilised €40 million (N$826 million), part of which will fund our 24% option from the Dutch government through Invest International.”

She insisted that “the investment is not paid by taxpayer money; it is a grant-funded investment, which lowers the overall cost of capital and ultimately the net cost to produce a kilogramme of green hydrogen”.

NORTH AFRICA’S ADVANTAGE TO EUROPE

While Namibia is part of the African Green Hydrogen Alliance formed in 2022, northern African countries like Morocco and Egypt hold a geographic advantage.

Their proximity to Europe, a major green hydrogen importer, gives them a leg up.

“The (north African) ability to undercut Namibia in the green hydrogen market would depend on how effectively they can leverage these advantages,” Hearn said.

She said factors such as the cost of production, market dynamics, policy support, and technological advancements would play a crucial role in determining their competitiveness.

“The marginal cost of Namibia’s hydrogen and derivative products will not determine its final market price. Instead, the interaction of global demand and supply will be a key driver in price setting,” she said.

Hearn said to achieve global decarbonisation goals from green hydrogen (estimated at some 500 to 650 million tonnes per annum by 2050), the challenge is not competition between countries.

“. . . but rather the ability to develop enough projects to meet this demand. Hyphen believes that Namibia will be among the three lowest-cost producers globally in what will be a very large market, which in the short to medium term we expect will be under supplied,” she said.

MAINTAINING SECRECY

Environmentalists, members of parliament and analysts have consistently called out the lack of transparency in the manner in which the Hyphen Hydrogen Energy Consortium was awarded the contract to develop one of the biggest green hydrogen projects in the world.

The project, initially valued at over N$190 billion, was negotiated with the Namibian government under a cloud of secrecy.

It is being developed in the Tsau //Khaeb National Park.

Some 1 050 plant species are known to occur in the park – nearly 25% of the entire flora of Namibia on less than 3% of the land area of the country.

Hyphen Hydrogen Energy is led by German company Enertrag and Nicholas Holdings.

Together they have a 40-year concession right to the project.

Hyphen and the government have both publicly refused to share what the contract entails or whether the government would offer any loan guarantees.

Raffinetti has said the government is best placed to answer this question.

Hearn said: “Feasibility studies are conducted by key market participants in various industries, the results of which are typically protected by the Bipa Act. The government is just one of many shareholders in the Hyphen project, which may or may not choose to make some of its feasibility results public.”

This is a global best practice, she said.

“However, some developers, especially the government-sponsored pilot projects, may be inclined to share their underlying assumptions,” she said.