What you need to Know:

- Falyali’s longtime head of finance, Cemil Önal, told OCCRP that these operations generated at least $80 million each month. (Reporters were unable to independently verify the figure.)

- Önal said he personally arranged some $15 million in “sponsorship” payments to public officials in Turkey and northern Cyprus each month.

- Reporters also found over $60 million worth of properties owned by Falyali’s widow in Dubai, which Önal identified as a major base for the alleged organization’s ongoing operations.

- The organization allegedly recruited thousands of people to open bank, credit card, cryptocurrency, and online payment accounts to move illicit gambling proceeds, according to Turkish prosecutors.

- The details laid out by Önal and Turkish prosecutors illustrate the difficulty of regulating illegal betting, a rapidly growing industry estimated to generate hundreds of billions of dollars a year.

Reported by OCCRP | February 13, 2025

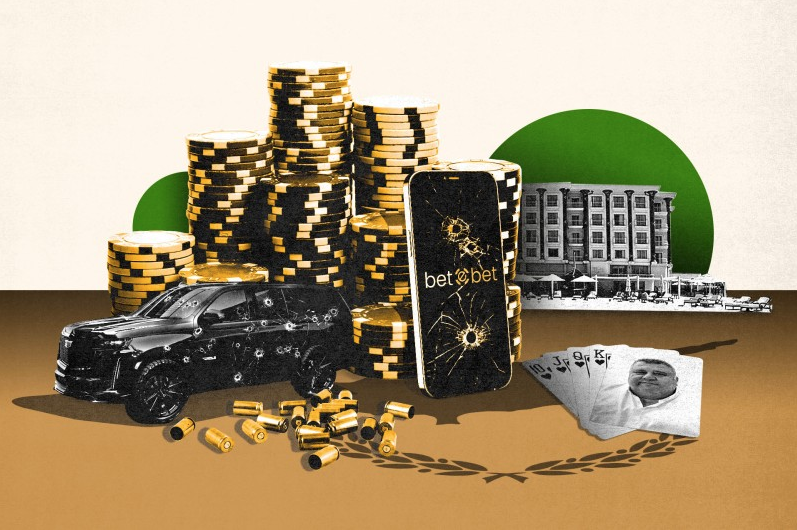

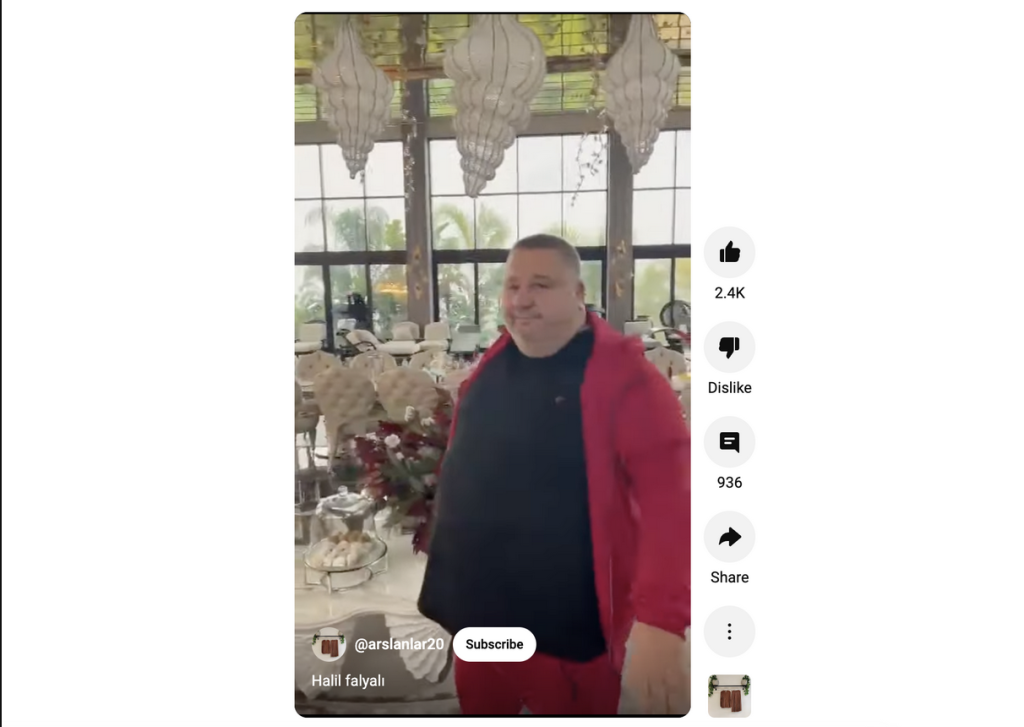

On a cool February evening in 2022, Turkish Cypriot businessman Halil Falyali was being driven home on a village road when he was ambushed. Attackers armed with automatic weapons unleashed a hail of bullets on his Escalade.

His driver fell dead behind the wheel. Falyali, a man built like a boulder, was still breathing when paramedics reached him, despite being shot multiple times. He was rushed to a local hospital — but within an hour he, too, was dead.

The killing sent shockwaves across northern Cyprus, the Turkish-backed breakaway region where Falyali had made his name. Breaking news alerts pinged on mobile phones, interrupting dinners. Social media posts quickly gained tens of thousands of views. “Night of Terror,” blared one newspaper headline. “Hearts are Broken,” declared another.

Publicly, Falyali had always portrayed himself as an ordinary businessman and hotel proprietor, albeit one with powerful connections. He was often photographed with senior Turkish Cypriot officials and never hid that he had close ties to the ruling National Unity Party, known as the UBP.

He also didn’t hide his wealth. Falyali regularly posted social media videos of himself driving dune buggies through his seaside estate, which featured a tropical garden, at least two swimming pools, and a fish pond for sturgeon, so he could farm his own caviar. His son appeared on YouTube posing with luxury cars, including a Rolls-Royce Phantom and McLaren 720S.

But behind the scenes, Turkish authorities had been looking into another aspect of Falyali’s business for years: An alleged illicit online gambling empire.

Ten months after the murder, in December 2022, Turkey’s interior minister held a press conference to declare a crackdown on what he said was a criminal organization running over a dozen illegal betting sites. Authorities had already seized over $40 million in assets from the group — but he said that was “just the beginning.” In December last year, Turkish prosecutors went on to indict more than 240 people, including Falyali’s widow, on illegal gambling and money laundering charges. The posthumous indictment accused Falyali of “establishing an organization with the aim of committing crime.”

The indictment is based on an unpublished 130-page report from Turkey’s finance ministry, obtained by OCCRP, which details the movement of payments from the alleged betting operation to a cryptocurrency wallet the investigators claimed belonged to Falyali.

As the trial moves through its early stages, another drama has been playing out — this one over a separate case involving Falyali’s longtime head of finance, Cemil Önal. In December 2023, Önal was arrested in the Netherlands on an Interpol warrant, issued at Turkey’s request, which described him as the man “in charge of Falyali’s money and finances” and claimed he was “one of the masterminds” of Falyali’s murder. He is now fighting extradition to Turkey, where he fears his life would be in danger.

Speaking from a Dutch prison, Önal told OCCRP he was not involved in Falyali’s death and insisted he was being targeted because he knew too much about illicit payments made to powerful people.

Officially, Önal worked for a Falyali-owned company that held a gambling license in northern Cyprus. But his real job, he said, was to help develop the illicit side of Falyali’s operations. By the time he stopped working for Falyali in late 2021, the alleged illegal gambling empire was making at least $80 million each month, employed hundreds of off-the-books workers, and oversaw thousands of betting sites aimed at gamblers in dozens of countries, Önal said. (OCCRP was not able to independently verify the specific revenue figure cited by Önal, but an expert who investigated similar networks in Asia said the volume was plausible.)

“I did not establish this system, this network for myself,” Önal said. “I established this system, this network for my boss.”

Önal said he personally funneled roughly $15 million a month into “sponsorship” payments on behalf of Falyali’s organization, mostly to ruling party officials in Turkey and northern Cyprus. Much of this was delivered in cash, he said, while some transfers were arranged through gold trading and foreign exchange shops, making it difficult to trace.

In over 20 hours of exclusive interviews, Önal laid out the workings of the alleged operation in unprecedented detail. While he was unable to provide documentation for his claims, journalists in a dozen countries independently corroborated many of them by hunting down company, property, and travel records, as well as law enforcement and court documents. They were also able to identify hundreds of websites set up by the alleged network. Experts confirmed that the model described by Önal closely resembled those found in other regions.

The 2022 Turkish finance ministry report listed around 100 cryptocurrency wallets it said were used by the group to transfer the “revenues of crime.” Using blockchain records, reporters found that these wallets have received more than $1.4 billion since 2018.

But these were just a fraction of the number of cryptocurrency wallets Önal says the network actually used. It also had other ways to move money around the world, including thousands of bank, credit card, and online payment accounts. (The finance ministry report said the group used over 1,500 bank accounts in Turkey alone.)

Using leaked property records and other documents from Dubai, which Önal identified as a major base for the network’s current operations, reporters also found tens of millions of dollars worth of properties owned by Falyali’s widow, Özge Taşker Falyali, who was among those indicted in 2024. She did not respond to questions about the source of the funds.

Turkish and Turkish Cypriot authorities did not respond to requests for comment.

Falyali’s Rise

The Mediterranean island of Cyprus is known for its golden beaches and ancient ruins. But the legendary birthplace of Aphrodite also has a darker side.

For half a century, the island has been divided by barbed wire and minefields between the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus and the breakaway north, which was occupied by Turkey in 1974 in response to a coup aimed at annexing Cyprus to Greece.

The north — whose statehood is recognized only by Turkey — does not fully adhere to international law and global banking standards. The territory has become a haven for fugitives and dirty money from around the world. It has also become a gambling hotspot, especially after casinos were banned in Turkey in the late 1990s.

The war displaced both Greek and Turkish Cypriots, among them the Falyali family. When Falyali was a child, they fled Paphos, a seaside area in the Republic of Cyprus, and eventually settled in the district of Iskele, in what is now northern Cyprus. He was in his late twenties when the gambling industry started to take off in the north.

By 1998, he had started working as a casino manager, according to his brother Hüsnü, who gave an account of the family history to Turkey’s HalkTV in March 2022, the month after Falyali was gunned down. In 2007, he said, Falyali took over Les Ambassadeurs Hotel & Casino, an upscale resort in the port city of Kyrenia, which is now owned by his widow and their 12-year-old son.

Though Hüsnü stressed that Falyali’s gambling operations in northern Cyprus were legal, he acknowledged that his brother had moved into illegal betting in Turkey as early as 2004. “However, it cannot be said that every illegal betting site belongs to Halil Falyali,” he added.

The legal side of Falyali’s operations were run by a company called Larsen Technologies Ltd., which was registered in 2013.

Turkish Cypriot authorities granted Larsen a gaming license to operate in northern Cyprus in 2017. The company opened walk-in betting shops under the brand BetCyp, and registered a namesake website, BetCyp.com.

But according to Önal, Larsen was a front.

“That was our umbrella. In other words, we were under the name of a legal company in case of a police raid, a financial raid or anything else,” Önal explained. Larsen also formally employed Önal between 2016 and 2020, corporate records confirm.

Website domain registration records obtained by OCCRP suggest the company may have indeed been connected to illegal gambling: Dozens of betting sites blacklisted by Turkey and the European Union were registered by the same email address used to register BetCyp.com. The website also shared a Philippines-based server with dozens more blacklisted sites.

Much like legal betting sites, these unlicensed sites offer live casino games, digital slot machines, and sports betting, customized to the language of the target audience and presented with eye-catching graphics. Gamblers can pay by credit card and cryptocurrency, or via various online payment platforms. Players, drawn in by aggressive advertising and generous bonuses, may not even realize they are betting on a platform that is not licensed or regulated in their country.

The companies behind the websites identified by OCCRP mostly displayed gambling licenses from Curacao. The Caribbean island nation had for years permitted a handful of locally licensed companies to issue “sub-licences” to operators abroad, allowing Curacao-licensed operators to proliferate globally with no oversight or legal right to operate in regulated jurisdictions.