RECAP: Up until now our series on money laundering has focused on the network around alleged money launderer Howie Baker, gold trader Andries Greyvensteyn and tobacco mogul Simon Rudland. In this instalment we take a closer look at a below-the-radar player in the notorious cash-in-transit industry that has moved huge amounts of money for an extremely shadowy clientele which includes international fraudsters, dodgy accountants, an alleged pyramid scheme and, seemingly, state capturers.

Back in 2011, a bizarre fraud was committed in the UK when Dutch shipbuilding magnate Edward Heerema was swindled out of millions of pounds by a gang of con artists.

Although the story is complex, it boils down to this: The alleged mastermind, Polish-Canadian Marek Rejniak, convinced Heerema that he was an agent of the US Federal Reserve with access to a mysterious VIP trading platform belonging to the Vatican and called the House of Aragon.

Heerema and his staff were sufficiently impressed by Rejniak and his collaborators’ fake personas to put up GBP100-million in order to earn supposedly outlandish profits on this unlikely platform. GBP16-million of that disappeared before Heerema managed to extricate himself from his quixotic “investment”.

Rejniak’s colleagues were eventually caught, but the man himself disappeared.

Investigators hired by Heerema chased tips and rumours around the world. Hong Kong, Singapore, Indonesia and Mexico were some of the places Rejniak allegedly cropped up, armed with a half-dozen passports and permanently packed suitcases.

AmaBhungane can add one more stop on that itinerary – South Africa, where Rejniak quietly showed up in 2015 as the sole director of a company named Atrum Investments.

And here the story takes a turn that leads us straight into Johannesburg’s “shadow banks” – cash-in-transit companies that in practice can also be used as wholesale clearinghouses for illicit money flows, while seemingly asking very few questions.

Registered at a modest office park in Krugersdorp, Rejniak’s Atrum pumped roughly R400-million into the operating account of one such cash-in-transit company – RENS Kontant in Transito – over a three-year period.

Additionally, the same people who set up Atrum for Rejniak created four more companies that likewise started pouring money into RENS – R3-billion of which we can see in our limited data – destined for cash delivery in Johannesburg and surrounds.

More on them below.

For a sense of scale, RENS handled at least R10-billion in the four years we have good data for, 2015 through to the beginning of 2019, and there is no reason to assume business has died off since then.

The takeaway is that RENS was effectively a nexus for questionable money flows, much like Asset Movement Financial services (AMFS), a rival cash-in-transit company we have dealt with extensively in this series.

The real question about these shadow banks, however, is: who needs to bank in the shadows?

Among those making use of RENS’ services were a number of entities implicated in spiriting away the spoils of state capture.

Others were allegedly major players in the illicit tobacco trade and yet others seemingly ran long-lived regional money-laundering networks, exchange control-dodging hawala schemes or, in one case, an alleged pyramid scheme.

In general, RENS served an astonishing variety of actors. In this it not only resembles AMFS but also other entities amaBhungane has investigated, and which we will deal with in due course.

What is particularly striking is how the clients of these large nexuses for money flows overlap. It is, we will show, a small world.

Before we dissect RENS’ clientele, however, some background is in order.

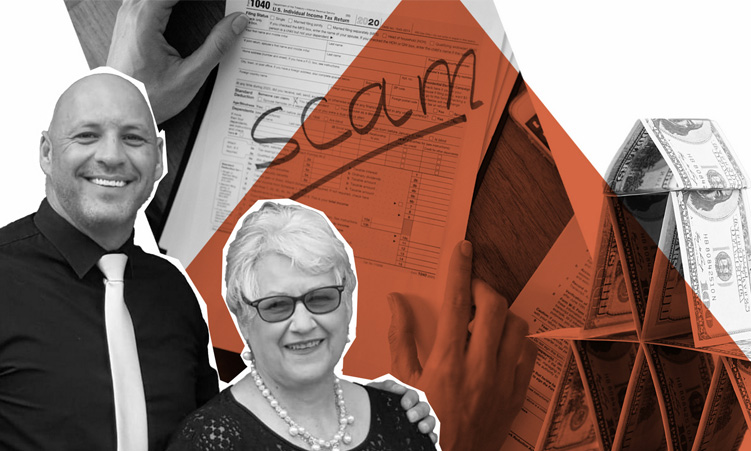

Christo and Kotie

RENS is run by mother-and-son team Christoffel and Jacoba “Kotie” Janse van Rensburg – the latter a former police officer and one-time board member of the Bond van Oud Polisiebeamptes, a social club for retired police officers.

RENS operates in an essentially identical way to AMFS, which we have reported on in a previous instalment of this series. Millions of rands are received daily in the form of either cash pickups or electronic transfers that get mixed up and then paid out, again via a combination of cash deliveries and electronic transfers.

Their commission was, in the period for which we have data, in the range of 0,3 to 0,5% of the money moved.

And as with AMFS, much of the money, at least on paper, comes from the gold industry.

By their own admission, however, The Janse van Rensburgs take very little interest in where money actually comes from or where it goes.

In a commission of inquiry held in Johannesburg in 2019 in relation to the disastrous looting of the Namibian Small and Medium Enterprises Bank, the two were grilled about a relatively small payment that made its way through RENS. They were questioned by advocate Raymond Heathcote:

[TRANSLATED FROM AFRIKAANS]

HEATHCOTE: So you receive the money. You don‘t know why you are getting the money?

JACOBA: No, I don’t know what he needs the money for.

CHRISTO: I mean, these guys are in the gold industry. Their clients often pay cash so I mean most of these guys do cash deals or that kind of thing

…

JACOBA: No, we don’t ask. We do the transaction with the client. We also have other clients. I mean I can’t, you know, ask every single client what they are doing with their money.

HEATHCOTE: Ask no questions and hear no lies?

CHRISTO: yes, almost something like that

JACOBA: Exactly…but at least not [entirely] no questions

The younger Janse van Rensburg later tried to dismiss this as a humorous exchange but also, in court papers, denied that the Financial Intelligence Centre Act even applied to the business. This is not true, as the act’s prescription to report suspicious transactions applies to everyone.

From RENS’s records it is clear that it has serviced a small core of clients but that each of these would be arranging payments from many different sources and to many destinations. They are, in other words, essentially brokers acting as intermediaries between RENS and the ultimate users of its services.

In response to questions, RENS’ attorneys accused us of acting “as if you were part of the various incumbent structures of the State investigating the incidents, which is of course not the case”.

“Kindly note our client’s stated position that it was at no stage wilfully or knowingly engaged in any illegal or nefarious conduct.”

They further demanded that we divulge the source of our information and provide copies of our documentation.

Their full response is available here.

Birds of a feather

We already touched on RENS in our previous instalment, showing how it received and paid onwards millions for better-known figures (including Howard “Howie” Baker) entangled in a massive money moving endeavour involving Aulion Global Trading, a Dubai-based company we introduced earlier in this series.

Altogether RENS paid R480-million to AMFS and other entities tied to Baker, essentially creating a double-layer of obfuscation between parties paying money and parties receiving money.

Of that, R83-million made its way to Saleem Ebrahim Attorneys, which in turn paid the money onwards to Prodigy Trading, a Hong Kong entity belonging to Baker.

Readers may recall that we previously exposed Ebrahim as the creator of a short-lived front company named Actinic Holdings, which likewise expatriated money for Baker.

(Ebrahim did not respond to our questions at the time, but in court papers SARS referenced his explanation that he denied wrongdoing and contended that he was merely acting on the instructions of his clients.)

We also showed how these payments were made at the behest of a RENS client named Baypass Logistics, which some references suggested had links to controversial Zimbabwean mogul Simon Rudland’s company Gold Leaf Tobacco Corporation, as well as, apparently, alleged tobacco smuggler Roy Muleya.

Our attempts to contact Muleya came to naught, while Rudland and Baker’s attorney denied any link and argued that the references to Gold Leaf in documentation and bank statements proved nothing at all.

Beyond AMFS, the recipients of the RENS money we can trace present an exotic mix of unlikely clients who appear to have little in common other than the need for moving improbably large sums of money.

The social entrepreneur

One more significant recipient of money from Baypass (via RENS) was a Sandton-based boutique “business development” consultancy named The Echelon Group, which received at least R161-million – the amount we can track for the period our banking data covers.

Importantly, The Echelon Group has also received smaller amounts from AMFS (as well as, more recently, several million rands from another Baker entity named Inracom, which we first reported on here).

It was, in other words, also, like many RENS clients, a client of the separate money-moving network around Baker.

The Echelon Group was founded by “social entrepreneur and philanthropist” Khanyisa Mothema and has, according to its website, counted among its clients the City of Joburg, the Industrial Development Corporation and the Development Bank of Southern Africa.

It has also “engaged various government departments in Zimbabwe on meeting their development funding goals”.

In Echelon’s bank statements we see the Baypass payments arrive, after which they mostly get distributed to a small set of beneficiaries identified by what appear to be initials.

We sent Mothema questions but received no response.

The dodgy accountant

Another consistent customer of RENS was controversial accountant Wolfram Landgrebe and his South African-Namibian firm WKH Landgrebe.

Landgrebe surfaced during the Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture (commonly known as the Zondo Commission) as an apparent channel for the dissipation of money from the infamous R2.65-billion PRASA contract that saw the country procure trains that were ill-suited for use on our rail network.

A first audit of money flowing from the tender was conducted by Ryan Sacks of Horwath Forensics and presented to the Zondo Commission in 2021.

With regards to Landgrebe, it was found that the small audit firm was paid R28-million by the winning bidder, Swifambo Rail Holdings, and also received indirect payments that had not been quantified at the time Sacks’ report was presented.

This total was raised to R30,5-million by a later audit commissioned by Swifambo’s liquidators. In addition, the liquidators found payments of R55-million to Landgrebe from another entity involved in the PRASA scandal, Auswell Mashaba Consulting Engineers.

This money was largely used to purchase property for Landgrebe’s client, the CEO and major shareholder of Swifambo Auswell Mashaba.

We can now shed light on some of Landgrebe’s wider operations.

Landgrebe’s firm paid over R130-million into RENS in the period our data covers. Before that it had also paid around R64-million into shadow bank AMFS, and before that it paid at least R44-million into Rustic Stone, AMFS’ predecessor.

Our interpretation of the accounts suggests that this money was destined for cash delivery to unknown recipients.

At both RENS and AMFS, Landgrebe was simply known as Wolf and records show that he earned a modest 0,05% commission on all the cash he sent RENS’ way.

According to a report by Open Secrets, Landgrebe was the subject of an investigation by the Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors. The board told us that this investigation is “ongoing”.

In response to our questions, WKH Landgrebe said that it does “not intend to respond to your interrogatories”.

Gys and Mauri

One major client in RENS’ books is Metal Enhancors, a refinery which, evidence suggests, has also been a major force behind the scenes of the local illicit financial system.

In our data we can see RENS make payments of over R620-million on Metal Enhancors’ behalf.

Seperately, as previously reported, Metal Enhancors was the source of an astonishing R2-billion sent to Inracom – yet another endeavour implicating Baker – illustrating how the clientele of companies like RENS and AMFS tend to use several conduits in parallel.

Back at RENS, Metal Enhancor’s recently deceased owner Gysbert Kriel was known as “Oom Gys”. We tracked down his widow, who professed complete ignorance of his business dealings.

According to RENS documents, the man in charge seems to have been one Mauri Swanepoel. Swanepoel seemingly also used RENS to channel millions into a company that liquidators have since described as a multi-million-rand pyramid scheme.

Layer upon layer

In May 2022 the Pretoria high court granted a liquidation order against Kadosh Finance.

According to an unopposed application by liquidators, Kadosh formed part of a complicated investment scheme run by Swanepoel.

It allegedly worked as follows:

Investors would be recruited to “lend” money to a first layer of conduit companies with promises of interest rates of up to 18%.

The “conduit” companies would then on-lend the money to Kadosh Finance, which would allegedly make enough profit from the purchase and exploitation of old platinum mine dumps to pay the conduits an astonishing 36% in interest.

According to liquidator Ralph Lutchman this arrangement “displays many of the hallmarks of a pyramid scheme” in that investors could only possibly recoup their money if yet more “lenders” came onboard.

This setup collapsed when Kadosh started missing repayments in 2019.

However, there was a lot going on behind the scenes that we can’t yet unpick.

Although payment references are somewhat inconsistent, we have determined that a minimum of R42-million was paid to Kadosh out of RENS while as much as R290-million was paid by Kadosh to RENS with the ultimate destination being unknown.

When liquidators convened an inquiry in terms of section 417 of the Companies Act, Swanepoel refused to appear.

He likewise did not respond to our questions.

All of the above, however, pales in comparison to the seemingly coordinated money-moving efforts of the companies we mentioned at the outset.

The mega-fronts

We earlier mentioned a company named Atrum, which had Polish fraudster Marek Rejniak as its initial sole director.

Atrum was one of five companies that were seemingly all set up by the same people and which collectively paid over R3-billion into RENS during the period covered by our data (which cuts off in early 2019), all for cash delivery.

In September 2015, not only Atrum but two of these brand new companies – Allmine Investments and Eventskiwido – started depositing millions with RENS on an almost daily basis.

Later they were joined by two more related companies: Femo Investments and Ceruphar Projects.

All five of the companies played musical chairs with a series of strange directors who amaBhungane have tried and failed to track down; some used Angolan, Zimbabwean and Congolese passports.

Rejniak was only a director at Atrum, but the companies are clearly connected.

For one thing, a seemingly random Johannesburg resident, Joao Camacho, suddenly appeared as a new director at all five companies in early 2017, with the previous directors simultaneously quitting. Camacho seems to have been a victim of identity theft.

Camacho’s wife says he had been robbed at gunpoint of, among other things, his ID shortly before the relevant period. His modest employment record at the time gives some credence to the explanation that he was an unwitting victim of identity theft. At least one other instance of likely identity theft took place, which means it is hard to confirm who is or is not a “real” director of these companies.

The situation at Atrum was particularly hard to follow. Rejniak’s successor Camacho was booted out and replaced first by Congolese citizen, Bwanachui Amisi and then by South African Eric Kasongo, about whom amaBhungane has not been able to learn much.

Finally, the cherry on the cake: much later, in 2021, Atrum, according to company records, passed into the hands of Ali Abdul Jabar Alseyed, a Ugandan citizen accused in that country’s media of gold smuggling and human trafficking.

The problem here is that Alseyed was long dead by then. He had reportedly been fatally shot in a Kampala hospital in 2019 by a member of his family whom he allowed to play with his own loaded gun.

Amazingly, apparently none of these companies littered with red flags had any difficulty getting bank accounts and transacting with millions of rands almost daily over the course of several years.

This is even more astonishing when considering that they were also registered at unlikely locations like a house in Roodepoort and a broken down old BnB in Germiston. These lowly premises and red-flag directors did not stop these companies from, as mentioned above, channelling several hundreds of millions of rands each into RENS.

Behind the scenes

AmaBhungane’s attempts to track down the common hand behind these companies led to a man named Muss Pascal. Both his cell number and another that appeared to be that of an employee were used in company registration documents as the contact details for the various untraceable directors.

This was confirmed by the shelf company vendor that originally registered the companies, who told us that “Muss Pascal presented himself to us as an agent authorised to facilitate the purchase and documentation” for at least three of the companies.

When contacted by amaBhungane, Pascal simply said “please leave me alone” before hanging up the phone.

This led deeper down the rabbit hole.

Pascal turns out to be the owner of yet another company we have encountered in our reporting on the region’s illicit financial system: Mirinc. We previously reported on a giant “hawala” that had been run through accounts at the defunct VBS Mutual Bank. Mirinc was one major channel through which this hawala was provided with cash.

Mirinc was previously known as Pinnacle Precious Metals Refinery. It appears to be part of the shadowy “second-hand” gold ecosystem we have dealt with extensively in this series.

Information obtained by amaBhungane shows that when Atrum, Eventskwido, Allmine and Femo made their multi-million-rand payments to RENS, these were in fact done on behalf of what was then still called Pinnacle (Ceruphar apparently fell into different hands).

This is evidenced by internal records tabulating weekly volumes of business from major RENS clients where deliveries for “PPM” are broken up into separate amounts for the four apparent fronts.

Pascal did not, however, own Pinnacle at the relevant time.

The then-owner of Pinnacle, Ridwaan Adams, responded to our questions with a denial.

“To the best of my knowledge and recollection, “PPM” had no direct dealings with these companies. “PPM” would certainly not have made payments to these companies as there was no working relationship with them.”

He mentioned that he had bought Pinnacle in 2015 and sold it to Pascal in 2019 – dates matching the payments to RENS.

To further confuse matters, the payments being made to RENS by Atrum, Allmine, Eventskiwido and Femo were apparently all ordered by an entirely different character who we will return to in another instalment – a wildly prolific dealmaker named George Markides.

Returning to RENS’ client book, however, we find more major conduits for funds to deeply suspect beneficiaries.

In particular, a close look at the books seem to show that investigators and researchers may have missed at least one channel through which the profits of Gupta-led state capture made their way out of the country.

More on that in our next instalment.