By Khadija Sharife and Silas Gbandia | 26 April 2016

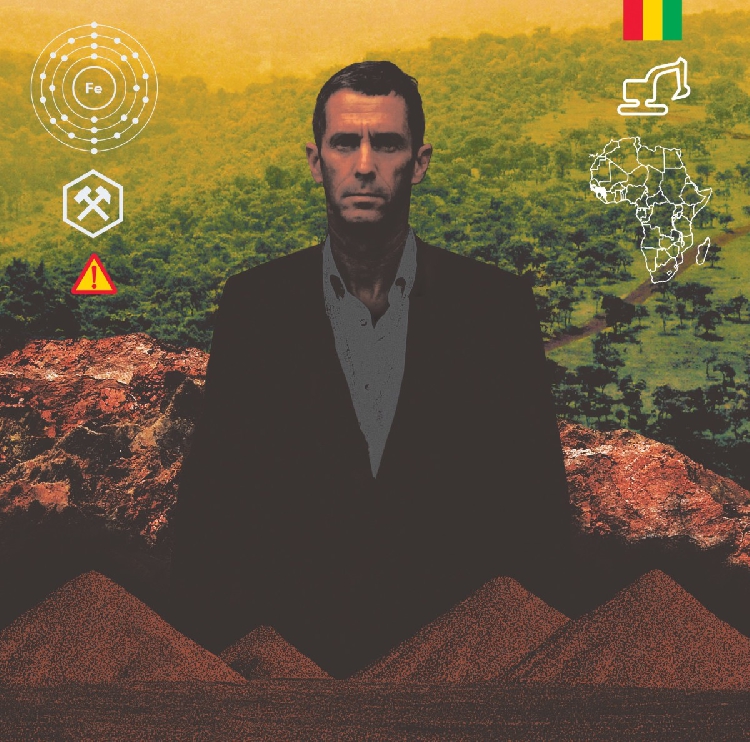

Given that profile, itrsquo;s not surprising that Beny Steinmetz and his eponymous company try to stay out of the limelight.

But with the Steinmetz Grouprsquo;s alleged tax avoidance scam in South Africa and an ongoing US grand jury investigation into corruption in Guinea, for the past two years, Steinmetz hasnrsquo;t been able to keep his name out of the headlines.

So, to avoid exposing the company, the embattled billionaire allegedly sold his 37.5% share in the Steinmetz Grouprsquo;s diamond segment, Diacore, to his brother, Daniel, in 2014.

Steinmetz left the Steinmetz Grouprsquo;s diamond business, Diacore, but has kept a business in Sierra Leone diamonds through the British Virgin Islandsminus;based entity Octea.

The company, which he runs through BSG Resources (BSGR), counts the Steinmetz family as beneficiaries. Unlike BSGR which operates in West Africa, Diacore maintains a presence in Namibia, Botswana and South Africa.

Leaked data from a Panamaminus;based offshore fiduciary Mossack Fonseca, shared by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and Germanyrsquo;s Suuml;ddeutsche Zeitung newspaper, sheds light on the internal financial structures created by BSGR to camouflage Octearsquo;s financial activities.

The data reveals a BSGR corporate structure, dated 2015, identifying Octea as wholly owned by Guernseyminus;based BSGR Resources ndash; the latter directly involved in the Guinea scandal. In turn, BSGR is owned by several foundations based in Liechtenstein and Switzerland such as Nysco and Balda.

Sierra Leone is one of Africarsquo;s leading diamond producers by value ndash; and Steinmetz, who reportedly had a personal fortune of $6 billion in 2012, is its biggest private investor.

According to World Bank sources, ldquo;for a long time, the national government calculated its forecast of national growth closely tied to the success of two companies, the BSGR and AML [African Mineral Limited]rdquo;.

Incomplete diamond export data, obtained by the African Network of Centers for Investigative Reporting (ANCIR), show that during some months from 2012 to 2015, Octea exported more than US$330 million in rough diamonds. Yet, although Octearsquo;s rough diamonds average $350 per carat, the company is alleged to be more than US$150 million in the red.

Dozens of creditors are waiting to be paid, including the government of Sierra Leone and Standard Chartered Bank. If these debts are not paid, the company could lose its license.

But some say this could be by design. Sources close to the company said the strategy was to exploit alluvial diamonds, feign financial struggles and leave creditors high and dry.

The company declined to answer questions about its financial practices, threatening legal action over issues it claimed were confidential.

Analysis of the available data raises many questions: Why canrsquo;t Octea pay its bills? How are the diamonds from Koidu mine valued?

Why doesnrsquo;t company data document the payment of taxes? And who in the murky diamond trade is Octea connected with?

Mine first

In 1995, the government of Sierra Leone entered into an agreement with the South African company Branch Energy Limited, an arm of Executive Outcomes (EO), a mercenary outfit that assisted governments across Africa with internal and crossminus;border wars.

The agreement, negotiated under the Mines and Minerals Act of 1994, was scheduled to last 25 years. Sierra Leonersquo;s military government handed over the Koidu mine to the firm in payment for helping to suppress the rebels during the countryrsquo;s civil war.

In 2002, the bloodshed ended, and the following year, a new agreement transferred rights, duties, and responsibilities from Branch Energy to Koidu Holdings, a company belonging to Octea of BSGR Resources.

Steinmetz was able to snag the mine for what was called a $28 million deposit, according to trade magazines such as JCKonline minus; a bargain for a mine that yields some the worldrsquo;s most valuable diamonds.

The government of Sierra Leonersquo;s new contract with Koidu Holdings, which would later be reviewed and renewed again in 2007, listed the terms: Koidu Holdings would pay a US$200,000 annual lease every year with a 3% increase from the prior year; income taxes of 35% would be deducted from Koidursquo;s net profit; the government would impose an 8% royalty rate for exceptional diamonds valued at more than US$500,000 per stone, with other diamonds priced on received sales value.

The agreement also stated that a government valuator would oversee the companyrsquo;s sorting and pricing process and granted the company the right to deploy armed security forces throughout the concession.

It also stipulates that on or before the 15th of each month, data concerning weight, value, size and categories of diamonds must be provided to Sierra Leonersquo;s director of mines and the Central Bank.

Firm connections

The data leak from Mossack Fonseca confirms a secretive financial structure connecting Koidu Holdings and Octea to wholly owned Steinmetz entities in Liechtenstein, the British Virgin Islands and Switzerland.

Some of these entities hold a great deal of money, especially when compared to Koidu Holdings, which had only US$5,401 in its HSBC account in 2007. That same year, Nysco listed $27.7 million in a single HSBC bank account. Benyrsquo;s brother and business associate, Daniel, was listed as attorney for an HSBC bank account with more than US$250 million.

Despite active diamond mines and money in its parent companies, Koidu Holdings owes more than $150 million in outstanding loans to Tiffany Co and Standard Chartered bank.

Loan agreements between Standard Chartered and Tiffany document floating and fixed charges in the form of diamonds from Octea. The exact nature of these payments is unknown. Neither Tiffany nor Standard Chartered responded to questions sent via email. Despite media reports, BSGR claimed it had not defaulted on the loans to either party.

The company has also failed to pay outstanding fees to the government of Sierra Leone minus; a situation that has threatened closure of the mine and contributed to the resignation of Octea CEO Brett Richards.

According to media reports, Richards encouraged GoSL to press for immediate payment from BSGR. It claimed it was not in arrears to GoSL.

Local incidents challenge BSGRrsquo;s denial. For instance, the mayor of Koidu city, Saa Emerson Lamina, stated to the author that Octea owed $700,000 in outstanding property tax.

ldquo;There is not a single iota of corporate responsibility,rdquo; he told us. In exchange for reduced taxes, the company pledged to provide a 5% profitminus;sharing agreement to the local community, and 1% of annual profits to the community development fund. None of this, said Lamina, has come to pass.

The companyrsquo;s financial difficulties do not appear to add up: During some months between 2012 and 2015, 987,000 carats were documented as exports by Koidu at a value of more than $335 million.

An analysis of Octearsquo;s exports show the company as producing 50% or more of Sierra Leonersquo;s annual exports.

The veracity of the data, say mining sources, is largely selfminus;regulated, with companies reporting their own exports in terms of volume and values. But it does suggest Koidu is one of Sierra Leonersquo;s most important exporters.

Disaggregated or monthly data by exporter reveals the company accounted for between 60 and 90% of all diamond exports in Sierra Leone.

But, unlike other companies, taxes for Koidu were never documented on available sources from 2012minus;2015. During September 2015, for instance, taxes were registered under all exporters except for Koidu, which exported about half ($9.5 million) of all exports ($19.5 million).

The previous month, Koidursquo;s exports accounted for $7 million of a total $9 million in exports; again, with no taxes documented.

Octea and Koidu Holdingrsquo;s financial accounts from 2012 to 2015 could not be accessed because they are incorporated in tax havens.

Nor could we access the costs of management services, staff, related companies and other critical details that comprise operations of business affecting preminus;tax profits.

BSGR Resources declined to answer questions pertaining to payments between subsidiaries and the purpose of specific entities that appear to be passive holding companies hosting only bank accounts and shares in other shell companies.

The company also threatened legal action.

There is also more than one Octea. Multiple variations, all incorporated in the British Virgin Islands, exist, including Octea Diamonds, Octea Limited, Octea Technical Services, Octea Mining and the like. BSGR did not clarify the different roles played by the companies.

The government department responsible for overseeing mining activity, the National Mineral Agency (NMA), declined to respond to questions.

Until 2005, the NMA, formerly named the Gold and Diamond Office, used a price book based on 1996 figures to value diamonds, creating room for potentially significant undervaluation.

Companies often lower their diamond value on exports to reduce taxes and externalize profits. Once exported to another foreign subsidiary where no taxes are owing, prices usually increase.

A third independent party, Diamond Counsellor International (DCI), is used to advise and check the pricing of diamonds alongside Octea and the GoSL. The company consults for governments in Liberia, Guinea, Angola and Sierra Leone.

The independent valuerrsquo;s price book is currently used by the NMA. This means two seemingly independent positions rely on one source.

The formulation behind DCIrsquo;s price book is not known; the company claims it uses industry contacts and market trends as source data. The price book complements the value placed on sales value by the company and the independent valuator, alongside the NMA.

A source formerly part of the Octea group said the companyrsquo;s management also had no idea how the company valued its diamonds, why diamonds were exported to Switzerland, or why the company was financially strapped.

Client 90618

It is not known whether Octea exports to Swissminus;based Diacore, now run by Benyrsquo;s brother, Daniel. Diacore is registered in Mossack Fonsecarsquo;s client database as client 90168 with more than an estimated 30 companies.

On the surface it appeared that Beny Steinmetz gave over control of Diacore, the grouprsquo;s diamond entity, to his brother Daniel.

An email dated January 2015 shows 50% of the company indirectly owned by Oceanview Trust (British Virgin Islands) under the beneficial ownership of Nir Livnat; 12.5% is indirectly owned by Zamaria Foundation (Liechtenstein) owned by Daniel Steinmetz; and 37.5% indirectly owned by Surfwave Foundation (Liechtenstein) also owned by Daniel.

But Beny appears to have retained power of attorney until June 2015. That is, until Diacore requested their fiduciary agent, Mossack Fonseca, to backdate the revocation of Steinmetzrsquo;s power of attorney to 2013. In a leaked email dated June 24 2015, (titled ldquo;PoA backdated 2013rsquo;) Mossack Fonseca states that it, ldquo;knows very well the situation of Mr Benny Steinmetzrdquo;.

The statement is made in response to Diacorersquo;s request: ldquo;We urgently want to finalize the cancellation and backminus;date the cancellation to the date mentioned in our initial request in 2013. The POA, dated 05.07. 2007, was not only issued to Benjamin Steinmetz but also to Daniel Steinmetz and Marc Bonnant.rdquo;

In a subsequent email, Mossack Fonseca confirmed to client 90168, Diacore, that it would consider backdating the 2007 power of attorney to remove Benyrsquo;s name and replace it with another.

Diacore claims maintaining Benyrsquo;s power of attorney was an accident and not a deliberate strategy for him to discreetly maintain control of the diamond company.

Undue Diligence

When asked to provide due diligence information for antiminus;money laundering requirements, Onyx, the Switzerlandminus;based advisers to the BSGRR, responded that the company supplied Tiffany, as if an association with the US jewelry brand precluded any wrongdoing.

Onyx claimed that ldquo;the above company is the owner of a diamond mining lease in Sierra Leone and has marketing engagements with Tiffany Co group companies.rdquo;

For its part, Tiffany told the media that it had done rigorous due diligence. Our questions were not answered by Mark Aaron, Tiffanyrsquo;s media spokesperson. The true state of Octearsquo;s finances remain unknown.