By Timo Shihepo | 2 October 2020

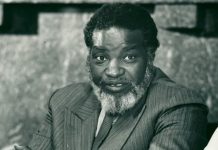

For years, suspended Fishcor boss Mike Nghipunya has earned the reputation of being a jack of all trades – a chief executive, economist, actor, and fashion designer. Now he is a corruption accused.

According to people who know him, Nghipunya (36) is a man who enjoys the limelight.

Among other things, this saw him donate N$50 000 from national fishing company Fishcor to help finance a movie in which he played a part.

The film, ‘Fish Out of Water’, released in 2017, features Big Brother celebrity Maria Nepembe as Maila, an escort who travels to Lüderitz for a better life. Maila encounters Nghipunya in the form of an enticing club owner named ‘Trust’, who asks: “You trust me?”

Now, the real man is accused in court papers of betraying public trust and faces allegations of corruption and money laundering involving N$75 million in fishing deals.

Nghipunya, who is in jail awaiting trial with two former ministers, Sacky Shanghala and Bernhard Esau, is painted as a Fishrot enabler.

He was allegedly involved in a questionable N$20 billion partnership between Fishcor and African Selection Fishing Namibia, co-owned by businessman Adriaan Louw and lawyer Marén de Klerk, who is accused of being the paymaster in the Fishrot saga.

The government now disputes the legality of that partnership and has ordered its termination.

Nghipunya was also involved in the purchase of a N$160-million fish factory for the Fishcor partnership, amid concerns that the government overpaid for the facility by as much as N$50 million.

SPENDER

Some describe Nghipunya as having a penchant for showering friends and business allies with gifts.

According to a close ally, ‘Tate Mike’, as he is known, at times carried lots of cash and flew around the world for fun.

He also invested in a fashion brand called TM clothing line, which sells sports gear and casual wear. It was launched in 2017.

“The clothing line was introduced for Namibia to notice this ‘young successful CEO’,” a friend who declined to be named told The Namibian.

The associate added that Nghipunya never hesitated to spend. “On outings, he would encourage people not to leave, as his tab was still open.”

Others described him as easy to get along with but difficult to read.

His brother Simon Nghipunya feels that Mike is a closed book to him. “I feel I am not in a position to speak on his behalf. I don’t think I know him very well. He must speak for himself,” Simon told The Namibian.

In May 2018, after The Namibian detailed allegations that Esau had spoon-fed Fishcor with a N$1,8-billion fishing quota deal over 15 years, Fishcor invited journalists to inspect its N$530 million horse mackerel processing plant at Walvis Bay.

The trip included a N$200 allowance for each journalist.

After the event, Fishcor organised a party at a hotel. When the dinner bill reached its limit, Nghipunya offered to pay the accounts of reporters. He settled the bill of about N$10 000 with his bank card.

Fishcor has over the years faced negative media headlines and it used public money in an attempt to clean its image.

For instance, it turned to public relations firms to portray itself as a company with good corporate governance.

One of them was Oxygen Communications, which raked in hundreds of thousands of Namibia dollars for three events over three years.

Managing director Hilda Basson-Namundjebo said Oxygen was appointed on the basis of proposals it submitted for each event.

One was the launch of a fishing vessel at Lüderitz, the second the launch of the Seaflower facility at Walvis Bay, and the third a media tour for 12 Namibian journalists.

“Different budgets were allocated for each event, with none exceeding N$200 000,” Basson-Namundjebo said.” The Lüderitz fishing vessel launch had the largest budget because we organised an event for the staff as well. Still, that event cost below N$200 000.

During Nghipunya’s tenure at Fishcor, the state-owned company backed the national hockey team with a sponsorship of N$1 million in 2016.

At the time, the national hockey team was led by Magreth Mengo, the fiancée of the chairperson of the Namibian Fishing Association, Matti Amukwa.

Amukwa is allegedly close to Nghipunya.

Amukwa distanced himself from the sponsorship, saying: “No ways – that is far from me. Me being at the Namibian Fishing Association has nothing to do with that sponsorship.”

Mengo said the sponsorship had nothing to do with Amukwa’s friendship with ‘Tate Mike’.

“Yes, I remember that sponsorship in 2016 but no, my boyfriend had nothing to do with it. It was handled via the hockey association,” said Mengo.

Namibia’s national women’s hockey coach Erwin Handura said he had known former Fishcor general manager Innocencio Verde since high school.

“We wrote proposals to many companies, but only Seaflower took a gamble with us. It paid off, because at the 2018 Indoor World Cup we won three, drew two and lost two games.

We set the standard so high and Seaflower’s investment was repaid.”

The national hockey team also received a N$40 000 sponsorship in the same year from Investec Investment Namibia, which was headed by James Hatuikulipi, who was former board chairperson of Fishcor and Nghipunya’s direct boss.

FISH OUT OF WATER

The director of ‘Fish out of Water’, Vickson Hangula, has been Ngiphunya’s friend since they were students at the University of Namibia (Unam). Hangula said despite Nghipunya’s colourful lifestyle, he was humble.

“The house he lived in at Lüderitz, the lifestyle he had … I was actually shocked that he’s the same person I was reading about in the papers. To me, he was just a friend. Since university, we were just boys who could lend each other money,” he said.

“We were young guys struggling to be actors. Life wasn’t easy. When he became a CEO, we remained friends but we hardly partied together. I’ve known him for over 10 years, but his other business dealings caught me off guard.

“For reasons known to him, he never discussed his other businesses with me,” he said.

Hangula added: “A young man is a young man. They’ll give hints here and there, like maybe buying an expensive bottle of alcohol or impressing young ladies. But not so that you would say he was flaunting money.”

Nghipunya drove a Kia Sportage SUV. “We still joke about it among our friends, saying this guy was loaded and we didn’t know about it,” he added.

On the film, Hangula said “I was looking for funds for the movie – its budget was N$1,2 million – and we received N$50 000 from Seaflower,” he said.

“When I told him we needed N$1,2 million, he offered to assist with crowd-funding from his ‘rich friends’, who wanted to remain anonymous. He helped us reach the target.”

The film is not publicly released yet.

HAND-PICKED

Born in 1984, Nghipunya grew up at Oshilungi village in the Oshikoto region. He later lived in Windhoek’s Freedomland.

He obtained a bachelor’s degree in economics from the University of Namibia in 2008.

Between July 2009 and March 2010, he worked as a regional statistician at the Namibia Planning Commission.

In April 2010, he moved to the fisheries ministry as a junior economist.

Then, in May 2014, the Fishcor board – led by former Investec Asset Management managing director James Hatuikulipi – appointed Nghipunya as acting chief executive of the national fishing company.

Former fisheries minister Esau and Hatuikulipi allegedly pushed for his appointment on the basis that a young executive was needed at Fishcor.

However, the move now appears to have been part of an orchestrated plan. Nghipunya appointed Hatuikulipi’s relative, Paulus Ngalangi, as Fishcor’s finance general manager in 2015.

Nghipunya was permanently appointed as Fishcor chief executive on a five-year contract.

During Nghipunya’s bail application in the Windhoek Magistrate’s Court in June, Anti-Corruption Commission investigation officer Willem Olivier said Nghipunya was hand-picked to run Fishcor as chief executive. He was paid N$1,5 million a year.

The Namibian understands that former deputy fisheries minister Samuel Ankama was one of the officials who questioned Nghipunya’s appointment at Fishcor.

Sources said Ankama, who taught Nghipunya at Iipumbu Secondary School at Oshakati, felt he was an average student who did not meet the requirements of the position.

“He was hand-picked. I like questioning things and I guess my colleague (Esau) didn’t like that,” Ankama told The Namibian last month.

“I questioned Nghipunya’s appointment but I was told it was only temporary. I then warned Nghipunya that he was maybe being used by my former colleague (Esau) without realising it.”

Ankama once wrote to the prime minister and president complaining about how Esau was handling issues surrounding Fishcor.

Esau allegedly told Ankama that he must stop complaining because the only reason he was deputy minister was because he (Esau) had assisted him.

Ankama eventually lost his position as deputy fisheries minister.

Hatuikulipi is said to have funded Nghipunya’s relocation from Windhoek to Lüderitz.

The house he lived in was allegedly renovated for about N$300 000.

A source said Nghipunya lived in a luxury house with top-of-the-range furniture and a private gym. The gym equipment is said to have been transported from Windhoek in a Fishcor vehicle.

FAME AND FORTUNE

Nghipunya owns several properties, including a house in Rocky Crest, Windhoek, which he says is valued at N$3 million, two flats at Freedom Plaza in the Windhoek city centre with a combined value of around N$5 million, and a property at Outapi which he tried to rent out to the Government Institution Pension Fund as its regional office.

The fund pulled out of the deal when Nghipunya was linked to the Fishrot scandal. He also has interests in Gwanyemba Trust, to which he sold a property at Omuthiya in 2019.

* This article was produced by The Namibian’s Investigative Unit. This article is part of profiles into key figures involved in the Fishrot scandal. Send us tips via your secure email to investigations@namibian.com.na