By Shinovene Immanuel | 13 May 2016

RUSSIAN billionaire Rashid Sardarov, who bought large tracts of land in Namibia, is among the long-serving clients of Mossack Fonseca, a disgraced law firm known for aiding the rich to hide their wealth in tax havens.

Absentee landlord Sardarov is a 60-year-old flamboyant Russian oligarch with an interest in energy businesses, property, aviation, hospitality and hunting wildlife for fun.

He bought several farms in Namibia measuring 28 000 hectares (around 28 000 football fields) in 2013 through his Switzerland-based company, Comsar Properties SA. Sardarov wanted to build a game ranch 70 kilometres outside the capital city Windhoek.

He is among high-profile business people exposed in the Panama Papers, an offshore leak which unveiled how the rich create offshore shell companies in tax havens to avoid paying taxes, conceal their riches and even engage in crimes such as money laundering.

Not all those exposed have necessarily committed illegal activities, but the secrecy of tax havens is increasingly coming under closer scrutiny. Sardarov did not answer questions sent to his company.

Data from Mossack Fonseca, leaked to German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), which in turn roped in other media organisations such as The Namibian’s investigative unit, shows Sardarov’s connections to the offshore world.

Mossack Fonseca specialises in creating offshore shell companies for the world’s richest and most powerful people.

Sardarov is one of Mossack Fonseca’s oldest clients, having bought Primavera Trading SA in 2000.

The company was formed in March 1999 by two fronting directors. Even though the company named in the Panama Papers is not the same firm which owns the land in Namibia, the existence of his offshore firm, Primavera, makes it possible for the ownership of the land to be transferred to Sardarov’s offshore company.

The secrecy of tax havens also means that it will be difficult to know whether an offshore company has bought into another firm, which would in turn pass on the ownership of the land.

According to leaked documents, Primavera was set up to carry on the business of an investment company and for that purpose to, among others, âbuy, own, hold, lease, sell, rent and develop land and buildings and real estate in all its branches, and to make advances upon the security of land or houses or other property or any interestâ.

The leaked data shows that in December 2013, 50% shares of Primavera were issued to Solidarity Alliance Foundation, which, according to documents found in the Panama Papers, is wholly owned by Sardarov. He directly retained his shares in December 2015.

During that period, Sardarov made several transactions, such as an interest-free loan to a Panama-based company called Tigron Corporation through Swiss banking giant UBS, a bank which admitted in 2009 to aiding the rich to avoid paying taxes.

The leaked data shows that Solidarity Alliance Foundation was linked to over 60 offshore companies.

Also, in 2015, officials representing Sardarov enquired about creating a Vistra Trust.

According to tax watchdog Tax Justice, Vistra Trusts allow the real owner of an offshore trust to have their cake and eat it, where they legally separate themselves from the assets (and thus are shielded from related taxes and scrutiny), yet still exert a significant measure of control.

Primavera Trading SA has a history of using front directors. Leaked data shows that on 20 May 2015, Primavera’s real owners Sardar Sardarov and Rashid Sardarov wrote a letter to Mossack Fonseca, asking the law firm to provide them with dummy company directors named as José Jaime Melendez and Lizet Moreno.

Those two, who served as directors of Primavera Trading before being asked to serve again, are known to be serial directors of offshore firms, having fronted for high-profile clients across the globe.

The Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism reported last year that Melendez manages more than 700 other offshore companies belonging to personalities around the world, while Moreno manages around 16 companies on behalf of other personalities registered in Panama.

The two are involved in a firm linked to a wealthy family, which is connected to Syrian president Bashar al-Assad.

The Sardarovs wanted the dummy directors to sign a US tax status declaration to be submitted to Belgium bank ING.

‘We, therefore, hereby declare that we will completely indemnify Mossack Fonseca or any other person commissioned by them against all and any consequences, lawsuits and/or damages which may arise in connection with any actions relating to the signature of the above-’mentioned document,’ the Sardarovs said in a leaked document.

One of the main purposes of creating an offshore company is to hide the names of the real owners. Even though creating these kinds of companies is not illegal, the Panama Papers once again showed that some of these shell companies, masked in secrecy, provide cover for dictators, politicians and tax evaders.

Namibian politicians have over the years tried to pass policies and laws which restrict foreign ownership of land, a commodity that has become one of the most expensive assets to acquire in a country of just over 2,4 million people.

Sardarov chairs Comsar Energy Group and his other company named Southâ’Ural Industrial Company (SUIC), two large private firms in Russia and in Eastern Europe.

The Centre for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo reported that Sardarov earned his first millions in Orenburg, a Russian region which borders Kazakhstan.

According to that report, he received a concession for mining natural-gas condensate that can be processed into drip gas to power vehicles, benzine and light distillate.

Sardarov used the refinery of Russia’s state-owned Gazprom until he built his own refinery when he established South Ural Industrial Company in Moscow in 2003, which now has assets worth US$2,2 billion.

He is unapologetic about his riches, and was quoted by the Centre for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo as saying he’s been loaded for years.

‘I’ve been a billionaire for years, and I’m not ashamed to say so’. He received Bosnian citizenship in 2011 because he was a major investor there.

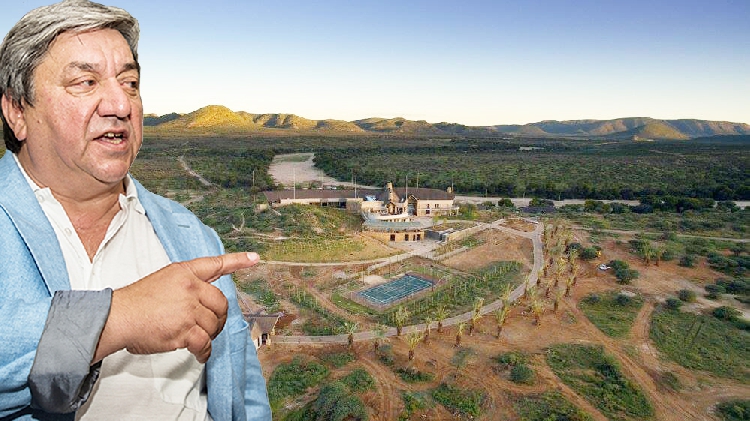

SARDAROV AND THE RANCH

Sardarov bought several farms in Namibia measuring 28 000 hectares in 2013 in the Dordabis area, situated 70km south-east of Windhoek.

By the end of 2014, Sardarov wanted to buy an additional 18 000 hectares of land for expansion. It is not yet clear whether Sardarov acquired the extra land he wanted. He is building a state-of-the-art ranch to be known as Marula Game Lodge.

A 2014 environmental impact assessment report seen by The Namibian said the Russian billionaire visited Namibia in 2006 on one of his many hunting trips to Africa.

That report also investigated the consequences of the game ranch, like the safety of the wildlife in the area as well as the communities and environment.

According to the environmental report, Sardarov owns the Namibian game ranch through Switzerland-based Comsar Properties SA, which in turn owns Marula Game Ranch Pty Limited together with Namibian partners named as the Popa Group. It’s not clear whether the Namibian partners still own the shares.

‘The idea of establishing the Marula Game Ranch and proposed lodge arose out of Mr Rashid Sardarov’s passion and love for nature and wildlife, particularly the pristine ecosystem of Namibia,’ the environment report said.

He claims that he wants to use the ranch to tap into the untapped Eastern, European, Middle Eastern and Asian affluent and high-spending tourists markets.

There were over 7 000 wild animals by 2014 on the ranch which Sardarov bought for N$72 million, and the area will keep around 15 000 animals once completed. The total investment by the Russian billionaire would be over N$700 million, claims the report.

Austrian media reported in 2009 that Sardarov owns a forest in Austria, where he âprotects the animals in this place with a fence from trigger-happy huntersâ.

He did not respond to questions sent to his company Comsar Energy via email. Mossack Fonseca told ICIJ and other media partners that it ‘does not foster or promote unlawful acts.’

It said it relies on middlemen whom it refers to as its ‘clients’ – bankers, lawyers and other operatives who feed it business – to make sure that people who get offshore companies through the law firm aren’t involved in criminal activity.

The law firm said it also has its own screening procedures, designed to identify suspect customers ‘to the extent it is reasonably possible.’

*This article was produced by The Namibian’s investigative unit in collaboration with the African Network of Centres for Investigative Reporting.

Email us investigative story tips: investigations@namibian.com.na