By Tileni Mongudhi

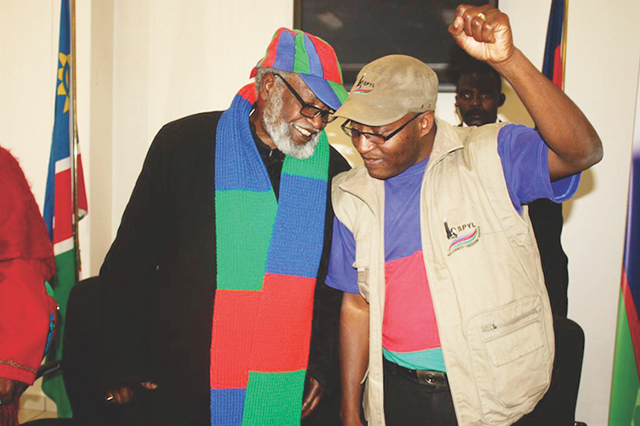

WHEN Swapo’s elite gathered five years ago for former president Sam Nujoma’s birthday, Elijah Ngurare, dressed in modest blue overalls, was there to welcome them to a party at a farm near Otavi.

The event, held at the Etunda Family Trust Farm owned by Nujoma, attracted the who’s who in Swapo’s power circles.

Ngurare’s mere presence was a remarkable signal of support for the firebrand youth league leader who just two weeks earlier had won a court battle, forcing Swapo to reinstate him as a party member.

Ngurare (51) had rankled party leaders with his outspoken criticism around the slow pace of rural development, and what he saw as inaction on creating jobs for young people.

Although he always treated Nujoma with deference, even reverence, he wasn’t afraid of annoying then-president Hifikepunye Pohamba.

His stinging tongue landed him in trouble. In 2015, the party’s top-four leaders forced him from his perch as Swapo’s youth leader, and then charged him, along with three others, with bringing the party’s name into disrepute, and with insulting party leaders.

Pohamba and his coterie had hoped that would silence him. Instead, he won the court battle and found himself back under Nujoma’s protective wing.

Their relationship was mutually beneficial. Ngurare spearheaded the 12 May Movement, an annual celebration of Nujoma’s birthday, which had fizzled out after he was ousted.

Asser Ntinda, former editor of Swapo’s newspaper, Namibia Today, says some at the party thought Ngurare was creating a cult of personality around Nujoma while securing his own future.

Ngurare became a political outcast. Attractive jobs bypassed him.

But after 10 years as a pariah, his fortunes began to change in 2021, and his possible return could be likened to the proverbial cat with nine lives.

After the ruling party was battered in the last elections, Ngurare is seen as someone who could help win back voters – even as a presidential contender for a party tainted by the Fishrot corruption scandal.

“Ngurare is the only one who can rescue Swapo,” says Ntinda.

But the people who orchestrated his ousting are still in charge of the party. At the height of his influence, Ngurare worked closely with Swapo’s then secretary general, Pendukeni Iivula-Ithana and presidential hopeful Jerry Ekandjo.

The two former ministers are now political outcasts.

Ngurare’s loyalty to one faction of party leaders became his undoing. Geingob and Pohamba allies dominated the politburo and endorsed Ngurare’s dismissal.

Ngurare was unmoved. He told Geingob that “I doubt you are qualified to judge me, because, to put it simply, my sins are younger than yours”.

Remarkably, the Ngurare-led Swapo Party Youth League (SPYL) championed the ‘guided democracy’ notion which played a leading role in Geingob’s re-emergence to the pinnacle of Swapo power in 2007.

Even after the High Court invalidated his dismissal in 2016, the Swapo leadership kept him out in the cold. Until now.

In the corridors of power, support is allegedly building for Ngurare’s return to the political fold. What’s unclear is if his old enemies have changed their minds.

“I am a civil servant,” Ngurare said when asked about his political ambitions. He refused to be drawn into any discussion about a possible presidential run. Since 2020, he has headed rural water projects at the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Land Reform, and he insists that is his only focus.

Allies of Ngurare have told The Namibian he would welcome a return to politics, but is wary of making any such pronouncements.

Civil servants are barred from actively participating in politics.

RASTA REBELS

Tjitunga Elijah Ngurare Manongo was born on 28 October 1970 at Nkurenkuru in the Kavango West region.

Some of his schools include Nkurenkuru High School, Shashipapo Secondary School, Rundu Senior Secondary School, and Kolin Foundation Secondary School at Arandis.

He joined Swapo in 1986, but had been active in politics since 1983 at Nkurenkuru High School. He was also part of a music group, the Rasta Rebels, at Kaisosi, Rundu.

After matric, Ngurare approached Geingob’s office in 1992, asking for financial assistance to study abroad.

Geingob – who was then the prime minister – allegedly declined to assist him at the time.

Ngurare went on to study water resources management in the United States, international comparative water law in the United Kingdom, and environmental law in Ireland.

After studying for a decade, he returned tech savvy that was novel at the time. He typed his own notes on a laptop while others still had secretaries doing that. He was an early adopter of social media, putting SPYL in front of young eyes.

When a corruption scandal forced Paulus Kapia out of the party in 2005, Ngurare took over the youth league, and focused its attention on expanding access to water, sanitation and housing.

He quickly started writing propaganda articles for Namibia Today, and served on the board of the party’s business wing, Kalahari Holdings.

He was involved in setting up the Swapo think tank and played a role in organising the party’s first-ever policy conference in 2012.

“This all formed part of his dream of making a difference in the lives of the poor,” says Henny Seibeb, deputy leader of the Landless People’s Movement (LPM).

At a time when others used politics to win instant business opportunities, Ngurare led a modest life.

He mostly lived in Swapo accommodation and drove a party car. He forfeited well-paying job opportunities his academic qualifications could have won him.

By 2004, Ngurare’s brand of politics had captivated the youth. He recruited stars like Gazza, The Dogg, and Girl Level to perform at party events – creating his own brand of ‘politainment’.

His focus on service delivery inspired fellow youth leaders to bluntly challenge Pohamba.

They also coined the mantra “we remain unwavering, uncompromising and patriotically stubborn”, when taking on senior politicians over a lack of service delivery.

‘A-LIAR NGURARE’

Not everyone was pleased with Ngurare’s rise in party ranks.

The late former youth minister, Kazenambo Kazenambo, who initially supported Geingob’s presidency, once rejected Ngurare’s re-election as youth league boss.

The late politician called Ngurare “a fake” and a “political ghost”, who appeared as if out of nowhere in 2000. The two would later reconcile.

In June 2013, Swapo hosted an extraordinary congress at Swakopmund with only one item on the agenda: whether 50/50 gender representation in all leadership structures is required.

This resulted in a historic triumph for women.

But the headlines were dominated by a sideshow, the near dismissal of the entire SPYL leadership.

On the eve of the congress, three reporters, including this writer, met with a few SPYL leaders at Swakopmund.

Discussions among them around politics became heated. Swapo had suspended the entire SPYL leadership and revoked their accreditation, barring them from the congress.

During the discussions, SPYL’s divisions were laid bare. Ngurare faced a mutiny. The splits aligned with divisions over whether to support Geingob for president, but also over Ngurare himself.

“All these problems are caused by A-liar Ngurare,” one youth leader said at that gathering.

That night, some of Ngurare’s own comrades accused him of being dictatorial, vindictive and manipulative.

But former youth leaders, such as Julius Nyerere Namoloh defended Ngurare. He said Ngurare encouraged open debate.

Ngurare was said to have spearheaded a purge of Rally for Democracy (RDP) sympathisers from the government.

Some alleged he had even prevented people from attending weddings and other social events for fear of being linked to the RDP.

‘HYPOCRISY’

Former NamRights director Phil ya Nangoloh says Ngurare is prone to hypocrisy.

“His behaviour is that of a person who says one thing and does the opposite,” Ya Nangoloh says.

“Personally he is not a bad person. Politically he is an intolerant demigod, however.”

He says he has told Ngurare that his spearheading of the 12 May Movement was “intolerant of other people’s views”.

Ya Nangoloh had squared off with Ngurare in 2007 after he made a submission to the International Criminal Court (ICC) that Nujoma be tried for war crimes over the deaths of Namibians in Swapo’s custody during the liberation struggle.

He claimed Ngurare had urged his subordinates to take up “bazookas and machine guns” against him [Ya Nangoloh] because of the petition to the ICC.

“It is wishful thinking for him to want to be president,” Ya Nangoloh says. “I view him as a general without an army. Ngurare does not have the required support base within the ruling party.”

THE DIE IS CAST

Around 2009, Ngurare almost faced charges for his proximity to the Children of the Liberation Struggle, also known as Exile Kids, who were demanding jobs at the time.

Three years later, he faced three new suspension motions at the SPYL central committee. In one instance a disciplinary committee was selected, but he survived all three motions.

Ngurare’s detractors again tried to vote him out at the SPYL 2012 congress. Namoloh was urged to challenge him, but declined to run.

“The youth league and its leadership were on top of their game when Ngurare was leading,” Namoloh said in January this year.

Some Swapo leaders linked Ngurare’s fall from grace to the Affirmative Repositioning movement, championed by three other youth leaders: Job Amupanda, Dimbulukeni Nauyoma, and George Kambala.

Swapo’s lawyer told the Windhoek High Court that Ngurare was the “ideological godfather” of the AR – a movement that aims to help the youth benefit from land reform – but Swapo’s top brass saw it as a threat.

The arguments did not hold up in court. But even after Ngurare won the case, the Swapo leadership kept trying to sideline him.

The onslaught continued with support from his deputy at the time, Veikko Nekundi.

Ngurare faced calls for his removal at the Swapo central committee and politburo.

Finally, in 2015 the die was cast: Ngurare was expelled without a disciplinary process.

He became an outcast and found refuge at the agriculture ministry.

His supporters were stigmatised and were purged from party structures.

With the Swapo congress looming, this year could either mark his political return, or signal more years on the political bench.

- This article was produced by The Namibian’s Investigative Unit. Send story tips via your secure email to investigations@namibian.com.na