By Sonja Smith and Eliaser Ndeyanale | 22 June

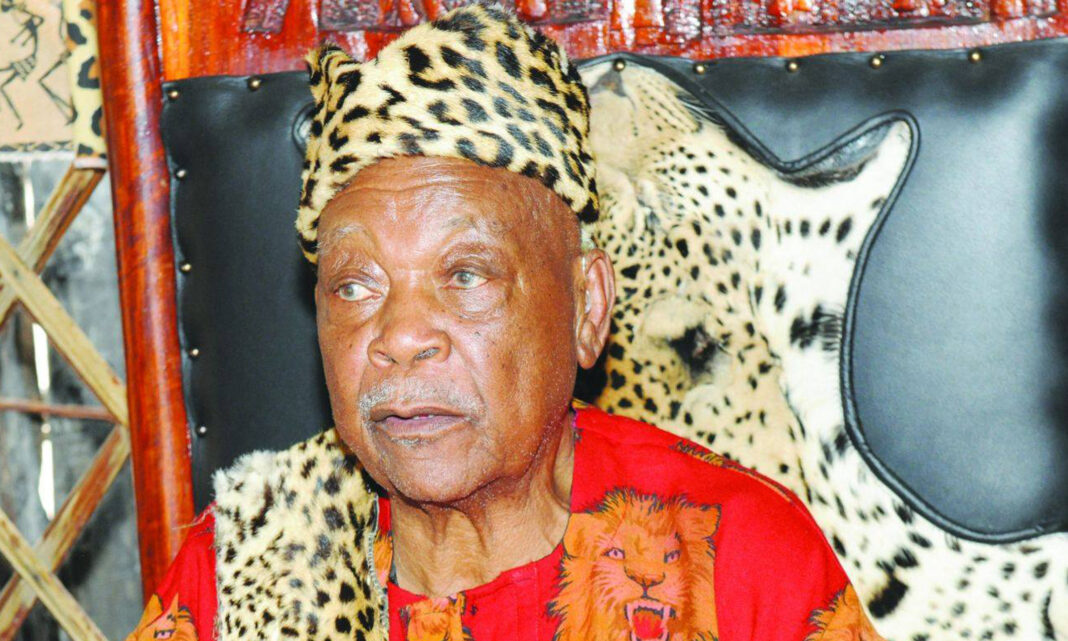

THREE years after Ondonga King Immanuel Kauluma Elifas died, his estate has still not been finalised.

His countless wealth of cattle and other assets is still being counted, his family and the executor of his will say.

Elifas ruled the Ondonga kingdom for 44 years, making him the kingdom’s third-longest serving leader, after pre-colonial kings Nembungu lya Mutundu and Nangombe ya Mvula, whose reigns lasted 70 and 50 years, respectively.

Elifas died in April 2019 at Onandjokwe State Hospital at the age of 86.

His 21-page will, obtained by The Namibian from the Master of the High Court, divides his thousands of head of cattle among his wife and descendants.

It’s unclear how much money was left by Elifas, since his estate is still being finalised.

Even with his herds spread across several villages, finding the cattle is easier than settling his financial affairs.

His will gives detailed instructions on how to divide the estate. But the actual herd is tended by a variety of relatives, loyalists, and paid cattle hands.

The delays in settling Elifas’ estate highlight the difficulties shared by people across the country, who grieve a death and then find their family’s assets tied up for years in legal proceedings.

Even though the king signed his will in 2015 and submitted it to the Master of the High Court in 2019, the process is still moving at a snail’s pace.

Finalising the will is far from over, according to its executor, lawyer Elia Shikongo.

“Some of the loved ones, and primarily his wife, were bequeathed assets other than cattle,” he says.

“Considerable time was expended towards locating such at various cattle posts with the assistance of both the police and private investigators, as a huge amount of cattle remain unaccounted for.”

As for any money or vehicles in the estate, Shikongo says they are still being “identified for listing”.

“The estate administration process includes identifying and listing all such assets, movable and otherwise, as may form part of the balance of the estate besides cattle,” he says.

“This is ongoing and includes following up with, among others, insurance companies and other institutions.”

The king’s will gives detailed instructions on how to divide his estate.

The main beneficiaries are his wife, Sesilia Helmut, his 12 children and his grandchildren.

Elifas’ son Shilongo told The Namibian in February his family had not seen the will yet.

“We have also not received or been given the cattle mentioned in it,” he said.

Elifas succeeded his late brother Fillemon Shuumbwa Elifas, who was killed by an unknown gunman in August 1975 at Onamagongwa near Ondangwa.

His brother was the chief minister of the Owambo administration at the time.

Elifas and Helmut got married in 1972. Four years later, they built their homestead at Onamungundo village when he took over the reign of the Ondonga kingdom.

That property goes to Helmut, the will says.

“There is nothing in our house that has been obtained from elsewhere by other means of acquisition, for example through inheritance.

“I have never inherited from any deceased person’s estate in my entire life other than as expressly stated in this will, as I do not like inherited things,” Elifas said.

He did, however, inherit cattle from his parents. He gave separate instructions for dealing with those animals, just as he detailed how to divide the cattle at each of the many posts where he kept them.

“My luck comes from my father and my mother. Everything I have comes from their blessings. I have everything I have been told to take care of by my father,” Elifas said.

CATTLE IN OTHER PEOPLE’S HANDS

It is not only family members who benefited from Elifas’ will.

The Oniipa Elcin Church and the Ondonga Traditional Authority have each received some cattle.

“I have been a cattle buyer with my wife, and we both like cattle,” the king wrote in his will.

But for as much as he liked cattle, he also liked to let other people tend to them.

Most of Elifas’ cattle are in other people’s possession, and the will goes into complex detail about who cares for which herd, and how each should be divided.

The king also divided land at Omangeti, which he received from the apartheid-era South West Africa government.

This land, Elifas said, is fenced off and divided into four camps. He directed that they be occupied by Helmut and some of their children.

The king’s will does not provide information on his business interests. Four years ago, the Ondonga royal court distanced itself from claims that Elifas owned 50% of a fishing company that partnered with Novanam.

“We are not aware if the king is truly a shareholder in that company, or if people are just using his name. We have been hearing such talk for a very long time that there are certain individuals who are using the king’s name to enrich themselves.

“We are following it up to make sure the king gets what belongs to him,” the king’s spokesperson, Naeman Amalwa, told Namibian Sun in 2018.

CHALLENGES

Wills in Namibia are regulated by the Namibian Wills Act 7 of 1953, as well as by customary law.

Ministry of Justice spokesperson Simon Idipo says the Office of the Master of the High Court receives countless complaints every day about the slow progress on liquidating estates.

The master is working with justice minister Yvonne Dausab to address these complaints and to speed up the administration of estates.

“We hope the discussions would result in a much-needed reform in laws governing the administration of deceased estates,” Idipo says.

Aside from the legal framework, disagreements and infighting between heirs are some of the main reasons why estates are delayed, he says.

Those whose estates have not been executed yet, include liberation struggle activist Otto Ferdinand Schimming.

Shimming died in December 2005.

A family member who spoke on condition of anonymity confirmed the estate has not been finalised 17 years later.

Former member of parliament Fillemon Moongo’s estate has also not been finalised seven years after his death.

Moongo, who doubled as the Omaalala headman, was a businessman who owned several supermarkets in the north, trading as Uukumwe.

He served as a member of parliament from 1994 until his death in March 2015.

Moongo’s daughter, Winnie Moongo, confirmed the estate has not been finalised yet and that the family is still waiting on their lawyer.

Shikongo highlights a delay in securing information from the deceased’s family as one of the challenges he is faced with in speeding up the process.

“A major cause in many is Covid-19, and pending administrations would have been office closures, limited working hours at the Office of the Master, as well as delays in securing cooperation or important information from family members,” Shikongo says.

He says this has been the case, with some estates still pending for over a decade.

“Those are normally related to the traceability of goods (cattle in this case), investments, policies and sometimes family disputes or queries,” Shikongo says.

“We have, however, mitigated (sic) against further delays and propose to execute earliest on the last wishes of his majesty . . . “

Elifas was buried at the Olukonda royal cemetery.

*This article has been produced by The Namibian’s Investigative Unit. Contact us via your secure email at investigations@namibian.com.na