ONE day during his presidential reminus;election campaign in September 1996, former US president Bill Clinton walked into a room in Westin Crown Center hotel in Kansas City.

At stake was a quarter million dollars in campaign fundraising. Clinton turned to his generous host, Farhad Azima, and led the guests in song. ldquo;Happy birthday to you, happy birthday to you….rdquo;

Azima, an Iranianminus;born American charter airline executive, had long donated to both Democratic and Republican administrations.

He visited the Clinton White House 10 times between October 1995 and December 1996, including private afternoon coffees with the president. Years later, as Hillary Clinton stood for election to the Senate in December 1999, Azima hosted her and 40 guests for a private dinner that raised $2 500 a head.

Azimarsquo;s Democratic fundraising activities provided an interesting twist in the career of a man who has found himself in a media storm of one of Americarsquo;s major political scandals, the Iranminus;Contra affair, during the Republican Reagan administration.

In the midminus;1980s, senior Reagan administration officials secretly arranged to sell weapons to Iran to help free seven American hostages then use the sale proceeds to fund rightminus;wing Nicaraguan rebels known as the Contras.

On a mission to Tehran in 1985, one of Azimarsquo;s Boeing 707 cargo planes delivered 23 tons of military equipment, the New York Times reported. Azima has always claimed to know nothing about the flight or even if it happened.

ldquo;Irsquo;ve had nothing to do with Iranminus;Contra,rdquo; Azima told ICIJ. ldquo;I was investigated by every known agency in the US and they decided there was absolutely nothing there,rdquo; said Azima. ldquo;It was a wild goose chase. The law enforcement and regulators fell for it.rdquo;

Now, records obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, the German newspaper Suuml;ddeutsche Zeitung and other media partners reveal new details about one of Americarsquo;s most colorful political donors. The records also disclose offshore deals made by another Iranminus;Contra figure, the Saudi billionaire Adnan Khashoggi.

The more than 11 million documents mdash; which stretch from 1977 to December 2015 mdash; show the inner workings of Mossack Fonseca, a Panamanian law firm that specialises in building labyrinthine corporate structures that sometimes blur the line between legitimate business and the cloakminus;andminus;dagger world of international espionage.

Spiesrsquo; offshore deals

The documents also pull back the curtain on hundreds of details about how former CIA gunminus;runners and contractors use offshore companies for personal and private gain.

Further, they illuminate the workings of a host of other characters who used offshore companies during or after their work as spy chiefs, secret agents or operatives for the CIA and other intelligence agencies.

ldquo;You canrsquo;t exactly walk around saying that yoursquo;re a spy,rdquo; Loch K. Johnson, a professor at the University of Georgia, says in explaining the cover that offshore firms offer.

Johnson, a former aide to a U.S. Senate committeersquo;s intelligence inquiries, has spent decades studying CIA ldquo;frontrdquo; companies.

The documents reveal that Mossack Fonsecarsquo;s clients included Saudi Arabiarsquo;s first intelligence chief who was named by a US senate committee as the CIArsquo;s ldquo;principal liaison for the entire the Middle East from the midminus;1960s through 1979,rdquo; Sheikh Kamal Adham, who controlled offshore companies later involved in a US. banking scandal; Colombiarsquo;s former chief of air intelligence, retired major general Ricardo Rubianogroot, who was a shareholder of an aviation and logistics company; and brigadier general Emmanuel Ndahiro, doctor turned spy chief to Rwandarsquo;s President Paul Kagame. Adham died in 1999.

Mossack Fonseca said they conduct thorough due diligence on all new and prospective clients that often exceeds in stringency the existing rules and standards to which we and others are bound,rdquo; said Mossack Fonseca in a statement.

ldquo;Many of our clients come through established and reputable law firms and financial institutions across the world, including the major correspondent bankshellip;If a new client/entity is not willing and/or able to provide to us the appropriate documentation indicating who they are, and (when applicable) from where their funds are derived, we will not work with that client/entity.rdquo;

WANNABE SPOOKS

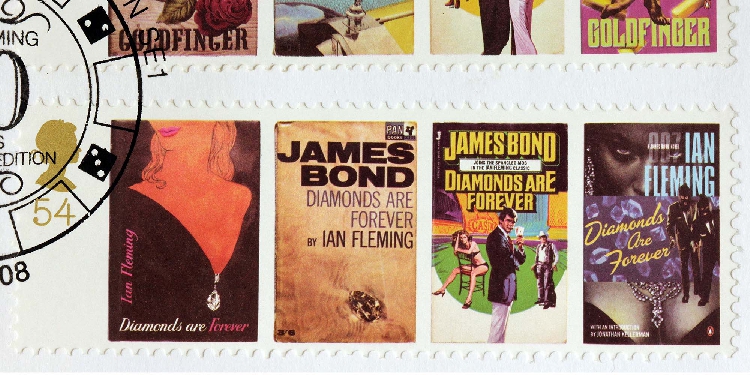

ldquo;Irsquo;ll suggest a name like ldquo;World Insurance Services Limitedrdquo; or maybe ldquo;Universal Exportsrdquo; after the company used in the early James Bond stories but I donrsquo;t know if wersquo;d get away with that!rdquo; wrote one financier to Mossack Fonseca in 2010 on behalf of a client creating a front company in the British Virgin Islands (BVI).

Universal Exports was a fictional company used by the British Secret Service in Ian Flemingrsquo;s James Bond novels.

The files further show that Mossack Fonseca also incorporated companies named Goldfinger, SkyFall, GoldenEye, Moonraker, Spectre and Blofeld after James Bond movie titles and villains and was asked to do the same for Octopussy.

There is correspondence from a man named Austin Powers, apparently his real name and not the movie character, and Jack Bauer, whom a Mossack Fonseca employee entered into the firmrsquo;s database as a client and not the television character after the employee ldquo;met him at a pub.rdquo;

But Mossack Fonsecarsquo;s connection to espionage is more often fact, not fiction.

Another colorful connection to the CIA in the Mossack Fonseca files is Loftur Johannesson, now a wealthy silverminus;haired 85minus;yearminus;old from Rekyavik, also known as The Icelander.

Johannesson is widely reported in books and newspaper articles to have worked with the CIA in the 1970s and 1980s, supplying guns to antiminus;communist guerrillas in Afghanistan.

With his CIA paychecks, The Icelander reportedly bought a home in Barbados and a vineyard in France.

Johannesson himself emerges in Mossack Fonsecarsquo;s files in September 2002, long after his retirement from secret service.

He was connected to at least four offshore companies in the BVI and Panama linked to homes in highminus;priced locales, including one located behind Londonrsquo;s Westminster Cathedral and another in a beachfront Barbados complex where a similar home is now selling for $35 million.

ldquo;Mr. Johannesson has been an international businessman, mainly in aviation related activities, and he completely rejects your suggestions that he may have worked for any secret intelligence agencies,rdquo; a spokesman told ICIJ.

AGENT ROCCO AND 008

Another connection to the Iranminus;Contra scandal is Adnan Khashoggi.

The Saudi billionaire, once thought to be the worldrsquo;s most extravagant spender, negotiated billions of dollars in weapons sales to Saudi Arabia in the 1970s and played ldquo;a central role for the US governmentrdquo; with CIA operatives in selling guns to Iran, according to a 1992 U.S. Senate report cominus;written by thenminus;Sen.

John Kerry, the Massachusetts Democrat who is now the U.S. secretary of state.

Khashoggi appears in the Mossack Fonseca files as early as 1978, when he became president of the Panamanian company ISIS Overseas S.A.

Most of his business with Mossack Fonseca appears to have taken place between the 1980s and the 2000s through at least four other companies.

Mossack Fonsecarsquo;s files do not reveal the purpose of all Khashoggirsquo;s companies. However, two of them, Tropicterrain S.A., Panama, and Beachview Inc., were involved in mortgages for homes in Spain and the Grand Canaries islands.

There is no indication that Mossack Fonseca investigated Khashoggirsquo;s past even though the firm processed payments from the Adnan Khashoggi Group in the same year that he made global news when the US. charged him with helping Ferdinand Marcos, president of the Philippines, loot millions. Khashoggi was later cleared. Mossack Fonsecarsquo;s files show the firm ceased business with Khashoggi around 2003.

SCARY STORY

In 2005, Mossack Fonseca employees learned with some alarm that someone on their books went by the name of Francisco P. Saacute;nchez, who Mossack Fonseca employees assumed to be Francisco Paesa Saacute;nchez, one of Spainrsquo;s most infamous secret agents.

ldquo;The storyhellip; was really scary,rdquo; wrote the person who first discovered Paesarsquo;s background. Mossack Fonseca had incorporated seven companies of which P. Sanchez was a director.

Born in Madrid before the outbreak of World War II, Paesa amassed a fortune hunting down separatists and a corrupt police chief before fleeing Spain with millions of dollars.

In 1998, Paesa faked his own death; his family issued a death certificate that testified to a heart attack in Thailand. But in 2004, investigators tracked him down in Luxembourg. Paesa himself later explained that reports of his death had been a ldquo;misunderstanding.rdquo;

In December 2005, a Spanish magazine reported on what it called Paesarsquo;s ldquo;business networkrdquo; that built and owned hotels, casinos and a golf course in Morocco. Without mentioning Mossack Fonseca, the article listed the same seven companies incorporated in the BVI.

In October 2005, Mossack Fonseca had decided to distance itself from the companies of which P. Sanchez was a director. ldquo;We are concern [sic] of the impact it may have in Mossfonrsquo;s image if any scandal arises,rdquo; the firm wrote an administrator to explain its decision to cut ties with P. Sanchezrsquo;s companies.

ldquo;We believe in principle that when a client is not up front with us about any facts that are relevant for his or her dealings with us, especially their true identity and background, that this is sufficient reason to terminate our relationship with them,rdquo; wrote a senior employee.

Paesa could not be reached for comment.

Two Names, Nine Fingers

Another internet search, this time in March 2015, alerted the firm that another of its clients ndash; a ldquo;Claus Mollnerrdquo; ndash; had been a customer for nearly 30 years. Among unrelated results from Facebook, a family tree or two and an academic linguistic review, there was one article from the University of Delaware.

ldquo;Claus Mouml;llner (the name that Werner Mauss always used to identify himself),rdquo; said the article.

Mollner or Mauss, also known as Agent 008 and ldquo;The Man of Nine Fingers,rdquo; thanks to the lost tip of an index finger, claims to be ldquo;Germanyrsquo;s first undercover agent.rdquo; Now retired, Maussrsquo;s website boasts of his role in ldquo;smashing 100 criminal groups.rdquo;

Colombian authorities briefly held Mauss in 1996 on charges, later dropped, that he conspired with guerillas to kidnap a woman and keep part of the ransom payment. Mauss claims the hostage takers were not rebels, that he never received ransom money and that ldquo;all operations carried out worldwide. . . have always been effected with the cooperation of German governmental agencies and authorities.rdquo;

While Maussrsquo;s real name never appears in Mossack Fonsecarsquo;s files, hundreds of documents detail his network of companies in Panama. At least two companies held real estate in Germany.

Mauss did not personally own any offshore companies, Maussrsquo;s lawyer told ICIJ partners Suddeutsche Zeitung and NDR public television.

All companies and foundations connected to him were to ldquo;secure the personal financial interests of the Mauss family,rdquo; Maussrsquo;s lawyer said, were disclosed and paid applicable taxes.

In the files it appears that in March 2015, a Mossack Fonseca employee clicked on the Google search result that linked Mollner to Mauss.

Yet there is no other suggestion that Mossack Fonseca discovered his true identity. His companies continued to be on Mossack Fonsecarsquo;s books into 2015.

It probably suited Mollner mdash; or Mauss mdash; just fine. As a journalist who interviewed him in 1998 observed, ldquo;The secret of his real identity was always Werner Maussrsquo;s capital.rdquo;

ndash; This article is produced by International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.