An investigation by The Namibian and UK-based journalism organisation Finance Uncovered revealed that the Australian multi-national mining corporation, Paladin Energy, pocketed N$665 million after selling shares in the Langer Heinrich mine through a Mauritius-based offshore company.

Paladin argues that using an offshore holding company means they are not liable to pay tax in Namibia.

Tax on the proceeds of the sale would have amounted to N$219 million.

When presented with details of the joint investigation, the Namibian tax office said they were unaware of the Langer Heinrich deal, but in their view, taxes should have been paid on the proceeds.

Tax bosses admitted that problems with legislation mean they are unable to enforce the law on offshore transactions like that of Langer Heinrich.

Conducting transactions through Mauritius as a way to avoid paying taxes on the profits when assets are sold, is a well-known tax avoidance loophole used by many companies around the world.

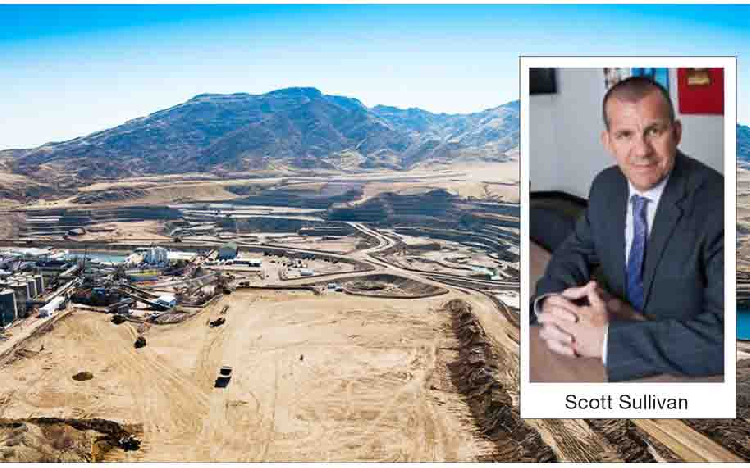

THE LANGER HEINRICH URANIUM MINE

The Langer Heinrich mine in the Namib Desert was once Paladin Energys jewel in the crown. Paladin bought the mine in 2002 from Aztec Resources Limited for a mere N$86 000, and an agreement to pay a production royalty of 12 Australian cents per kilogramme of yellow cake sold was struck.

At the time, Langer Heinrich was little more than an empty piece of desert land. Attempts by Aztec Resources to develop the mine came to nothing due to the weak world uranium prices in the late 1990s. But by the time Paladin took over, uranium mining was once again the future.

Namibia is the worlds fourth-largest uranium producer, which is mainly used in nuclear power plants, and to manufacture nuclear weapons.

When Paladin acquired the mine in 2002, it immediately commissioned studies and plans, with construction starting in 2005.

The company set aside N$585 million to develop the mine, which was opened by former president Hifikepunye Pohamba in 2007.

Subsequently, the mine underwent two expansions – to improve capacity – and by 2014 was producing 5,6 million pounds of yellow cake a year, which would have been worth at least US$159 million on the international uranium markets.

THE DEAL

In 2011, the disaster at the Fukushima nuclear plant in Japan saw world uranium prices plunging, and by 2016, they had hit an 11-year low.

However, Langer Heinrich remained a valuable asset for Paladin. Three years after the Fukushima disaster, Paladin sold a 25% stake in the mine to the China National Nuclear Corporation for about N$2 billion, netting the company a healthy windfall, and they recorded a N$665 million profit – attributed to the sale of its shares.

However, not a cent in tax on this profit was paid to the Namibian government.

Disclosures by Paladin under the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative show that the company paid nothing in corporate tax to the Namibian government that year, although it paid N$101 million in payroll taxes and mineral royalties.

The N$219 million lost to the government is enough to pay for the construction of 35 112 toilets in Namibias rural areas.

CAPITAL GAINS

Until 2011, Namibia did not tax capital gains – the profit made when an asset is sold. The Income Tax Act of 2011 introduced a tax on profits from the sale of shares in a company holding a mining licence.

This tax was reduced from 34% to 33% in 2014, the year the Paladin sale took place. Had this been applied to the sale of Paladins shares in Langer Heinrich to the Chinese, the company would have had to pay N$219 million in tax.

For their part, Paladin claims no tax was due because instead of selling shares in the Namibian company operating the mine, it sold shares in the Mauritian holding company. Mauritius does not charge capital gains tax.

Paladins chief executive, Scott Sullivan, told Finance Uncovered: “Paladins investment in Langer Heinrich Uranium (Pty) Ltd, which owns the mineral licence for the Langer Heinrich mine, is ultimately held through Paladins subsidiary Langer Heinrich Mauritius Holdings Limited (LHMHL), which is a Mauritius-domiciled company.”

He said: “The 2011 act did not apply because Paladin sold 25% equity interest in Langer Heinrich Uranium (Pty) Ltd to China National Nuclear Corporation. There was no sale of Langer Heinrichs Namibian mineral licence, nor was there any sale of shares in a company for a mineral licence.”

Sullivan denied that the Mauritian entity was established to avoid paying taxes in Namibia. He said the company was set up in 2006, years before Namibia introduced a capital gains tax on mining rights.

“Please note that this group structure was established almost six years before the amendments mentioned above to the definition of gross income contained in the 2011 act, and that offshore group holding structures are used by the industry worldwide.”

However, research by The Namibian found that although Langer Heinrich Mauritius Holdings was established in 2006, the company only appears in Paladins accounts from 2011.

This appears to indicate that the company was inserted into the corporate structure in response to Namibias attempts to tax profits on the sale of mining interests.

Sullivan claimed that the structure was not tax-driven.

“This group structure was established in 2006, for the purpose of holding Paladins investment in Langer Heinrich to enable project financing by foreign banks (without which project financing would not have been available, and the project with all its investment, employment and benefits would not have been built), and to provide specialised management and uranium marketing services to Langer Heinrich,” Sullivan stated.

According to Tax Justice Network Africa executive director Alvin Mosioma, companies like Paladin have been involved in “aggressive tax planning schemes” that leave most countries unable to collect enough revenue, primarily through Mauritius which has countless tax treaties with most countries.

A LACK OF ENFORCEMENT

While Paladin insists that no tax was due on the sale of shares, the Namibian tax office takes a different view.

After seeing the results of our investigation, Namibias commissioner of inland revenue, Justus Mwafongwe, told The Namibian “the place where the sales transaction takes place is irrelevant”, and “we agree that the indirect disposition of the shares by the investor should have been taxed in Namibia”.

Mwafongwe said they were unaware that the transaction had taken place since the Namibian tax system was a self-assessment system: this means the obligation was on companies to self-report their tax liabilities. This suggests that Paladin had not informed the Namibian tax authorities about the deal.

“We dont have legislation that compels companies to disclose changes in their shareholding structure. It is, therefore, difficult to know when these transactions occur, unless it is where they state it in their financial statements.”

However, the taxmans office said they lack enforcement mechanisms to hold offshore companies liable for Namibian taxes.

“A tax authority is usually challenged in enforcing these kinds of provisions because the company liable for such tax may not have any assets in the taxing jurisdiction.”

The mine was closed this year, waiting for a pickup in world uranium prices, forcing significant job losses at the plant.

The tax commissioner said government efforts are at an advanced stage of changing the law which will address how to enforce capital gains tax on indirect transfers where both the buyer and seller are offshore.

Options include requiring buyers to withhold part of the transaction fee to pay the tax, or placing the liability on the local company – all of which will come too late in the case of the Langer Heinrich transaction.

* This article was produced by The Namibians investigative unit in partnership with Finance Uncovered.