By Margot Gibbs | 21 July 2020

LEAKED documents and the affidavit of Fishrot whistleblower Johannes Stefansson suggest that seafood company Samherji used a host of techniques to ship revenue out of Namibia and reduce its tax bill in the country.

These include sending at least N$93 million in controversial “fee” payments to the group’s other companies in low-tax Mauritius and the UK, and selling fish below market prices to group companies in Cyprus.

Samherji is also accused of colluding with senior political and business figures in Namibia to gain preferential access to the country’s lucrative fishing grounds.

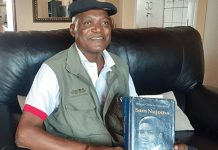

In a lengthy affidavit provided to Namibia’s Anti-Corruption Commission, former Samerji’s employee Johannes Stefansson claims Samherji moved significant revenues to group companies in what he believed to be a tax-avoidance scheme.

Stefansson was once the managing director of Samherji’s companies in Namibia, but he is now working with authorities in the country on a criminal investigation into what has been dubbed the “Fishrot” scandal.

An analysis of the leaked files as well as public documents and the company’s financial statements suggest Samherji used a number of techniques to reduce taxes in Namibia.

These include Samherji’s Namibian companies sending at least N$93 million as controversial “fee” payments to the group’s other companies in low-tax Mauritius and the UK, and selling fish below market prices to group companies in Cyprus.

In his affidavit, Stefansson also alleges Samherji overcharged its Namibian company for the cost of chartering trawlers, a strategy that he says shifted profits out of Namibia and reduced its tax bill.

Samherji, one of Europe’s largest fishing companies with annual revenue of about N$11 billion, first entered Namibia in 2012.

After landing a deal two years later with a state-owned fishery that awarded it lucrative quotas to catch horse mackerel, it quickly grew to become one of the biggest players in an industry that brings in a fifth of the country’s export earnings.

Samherji, however, strongly denies any wrongdoing, citing it was doing what is normal for multinationals.

Its current co-CEO, Björgólfur Jóhannsson, said there were legitimate business reasons for all the transactions raised, arguing that it is standard practice for multinational companies to use specific subsidiaries to legally minimise legal, tax, and operational risks.

He said Samherji had allocated “substantial” resources to investigate its operations in Namibia since the Fishrot scandal broke and launched a compliance programme to improve governance across all the group’s companies. But Jóhannsson declined to comment on detailed allegations in this article until an internal legal review was complete.

FEES, FEES AND MORE FEES

While there has been widespread reporting about similar schemes used by oil and mining giants in Africa, until now there has been little focus on one of the continent’s most precious natural resources – fish.

One of the key ways in which Samherji appears to have reduced its taxable profits in Namibia was by sending hefty fees to its companies in other jurisdictions.

Although Namibia’s corporate tax rate of 32% is standard for southern Africa, it is higher than in many European states and tax havens. The equivalent rates in the UK, Cyprus, and Mauritius are 19%, 12,5%, and 15%, respectively.

Leaked invoices and contracts suggest Samherji’s Namibian entities paid around N$93 million to group companies in the UK and Mauritius for management, intellectual property, and marketing.

Emails between Samherji’s chief accounting officer, Ingvar Juliusson, and a local lawyer, discuss setting up a new corporate structure to channel royalty payments out of Namibia.

According to leaked emails, these payments appear to have been part of a plan to extract profits from Namibia. Stefansson, the whistleblower said that neither the UK nor the Mauritius firm provided any services to the Namibian firms.

This is borne out by a 2014 email in which Juliusson wrote to lawyer Andrew Theunissen of Theunisen Louw & Partners seeking advice on a new corporate structure.

“What we are looking into is channeling [sic] the royalties derived from our Namibian operation out of Namiba[sic] to Mauritius,” he wrote. “Can you please provide reccomentions [sic] on how to structure this and your advise on how to do this properly.”

Juliusson told the lawyer the royalties would be for “access to technical know-how, etc. Advise on how to describe this would be welcomed.”

Part of an email exchange between Juliusson and a lawyer describes the company’s desired corporate structure, in which large fees would be sent offshore to Mauritius.

In March 2015, Samherji became the shareholder of a newly minted Mauritius company, Mermaria Investments. An agreement was drawn up that gave the Mauritius company rights to 5% of the net revenues of one of the companies Samherji part-owned in Namibia.

These payments, according to the agreement, were supposed to be in exchange for “know-how, management experience and good management team, including staff, sales people, directors and others and for the use of the internationally established brands.”

An invoice for millions of Namibia dollars in royalties to be paid to Mermaria Investments, the new company set up in Mauritius with Samherji as a shareholder, from ArcticNam, one of the companies Samherji part-owned in Namibia.

According to invoices and payments records seen by Finance Uncovered, at least N$55 million was sent to Mermaria Investments in Mauritius as “royalty payments” under the agreement.

Mauritius is a leading African tax haven that has played a huge role in tax dodging on the continent and beyond.

A similar set of internal agreements found in the Wikileaks files appear to have underpinned payments of N$38 million in 2012 from a second Namibian company to Onward Investment Ltd, a Samherji firm registered in the UK.

These agreements included a “management” fee equivalent to 5% total revenue and intellectual property licensing fees amounting to 50% profit before tax.

Riva Jalipa, Policy Lead at Tax Justice Network Africa, says that companies frequently pay royalty or management fees to affiliated companies in low-tax jurisdictions like Mauritius to reduce taxes in countries where they generate the bulk of their profits.

She said multinational food companies that tried to minimise tax payments in their operating countries were “rigging the system.”

“Not only do they deprive governments of tax revenue, they also get unfair advantages over local companies,” which are unable to send profits offshore.

Samherji’s co-CEO, Jóhannsson, said their companies had paid N$120 million in corporate income taxes over the eight years it operated in Namibia and N$400 million in other payments to the state, such as withholding taxes and export taxes.

Samherji invoices also suggest its profits in Namibia were being deliberately eroded by selling the fish it was catching in African waters to its own trading company in Cyprus at what appear to be artificially low prices.

The documents, which show the amount at which Samherji sold its fish from Namibia to Cyprus, then from Cyprus to clients in the Democratic Republic of Congo, suggest these discounts were between 10% and 20%. The Cyprus company then sold the fish at market rates, thereby reaping superprofits.

“Multinational companies use specific subsidiaries for specific transactions to minimise the spread of legal, tax and operational risk,” said Johannsson, the Samherji CEO.

* This article is supported by the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and UK-based Finance Uncovered.