By Tileni Mongudhi | 12 November 2021

IN 1996 Sacky Shanghala was muscling his way into student politics at the University of Namibia (Unam).

He joined a commission looking into an embezzlement scandal which the student representative council (SRC) was allegedly involved in.

The commission never found conclusive evidence of wrongdoing, but nonetheless ejected individuals tainted by the scandal, and brought in fresh blood – a promising start to the young Shangala’s political career.

Yet, as his star rose, his orbit shifted, pulled by his seemingly endless desire for material wealth.

Ten years after the SRC scandal in Windhoek, he was in a boardroom with one of the ousted council members, James Hatuikulipi, and one of the reformers, Leevi Hungamo.

In the boardroom, they were all on the same side, presiding over a multimillion-dollar business empire that relied heavily on government contracts.

Fast forward another 13 years, and Shanghala and Hatuikulipi were both arrested for their role in the Fishrot corruption scandal, the biggest corruption scandal in Namibian history, costing Swapo its supermajority in parliament.

During his 10 years in high political office, Shanghala has been linked to more than 15 questionable state transactions worth more than N$13 billion.

Now, the man once seen as a future presidential candidate is in a holding cell at the age of 44.

SON OF A BISHOP

Sakeus Edward Twelityaamena Shanghala was born on 13 June 1977 at Outapi into a prominent family, marked by the liberation struggle.

His father, Josephat Shanghala, is a respected retired bishop in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Namibia (Elcin).

ONIIPA, 09 August 2013 – Bishop Josaphat Shanghala of the West Diocese of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Namibia (ELCIN) pictured in Oniipa on Friday. (Photo by: Mathias Nanghanda) NAMPA

His mother, Ndamona, was a senior nurse at the Oshakati State Hospital, who died in the town’s notorious bank bomb blast of 1988.

The liberation hero bishop Kleopas Dumeni and his wife, Aino, are his godparents. The two clergymen are close friends, and Shanghala looked up to Dumeni as a mentor.

After graduating from the prestigious Oshigambo High School, Shanghala walked through Unam’s gates with one mission: to become a lawyer.

He had a passion for human rights, and in 1997 landed an internship with the Namibia Non-Governmental Organisation Forum (Nangof).

“At university, Sacky was not into partying, alcohol, and women like other male students,” a former student friend says.

“He was more chilled and laid back. We even used to make him our driver when we went out drinking around Windhoek.”

Shanghala and fellow lawyer Sisa Namandje once had a radio slot with the NBC’s Katti FM (then Oshiwambo Radio Station) on which they educated listeners on wide-ranging human rights and legal issues.

Everything changed when, halfway through his internship, Shanghala crossed paths with Hage Geingob, who was then Namibia’s first prime minister.

Geingob was so impressed with Shanghala that he hired him as a special assistant.

His political and business fortunes rose in tandem. Never media shy, he developed a taste for expensive wine, whiskey, and fine cigars.

He flaunted his wealth, dressing in tailored suits that he accessorised with expensive cufflinks, Rolex watches, Mont Blanc pens, money clips, and neat spectacles.

He owns six vehicles, including a Jaguar, two Mercedes-Benzes, a Toyota Fortuner, a Land Rover Discovery, and a Range Rover 5.0.

He took pride in how he articulated Queen’s English so well that it intimidated people.

BROTHERS

Shanghala’s rise to wealth and power was closely tied to his friendship with Hatuikulipi.

At a glance, they seemed like opposites.

Shanghala was the reserved, book-smart child of a clergyman. Hatuikulipi was a confident, street-smart young man, equally comfortable on the streets of Windhoek and Katutura.

They bonded at their residence, with their rooms in their hostel less than 10 metres apart.

Later in life, they became inseparable. They worked different day jobs, with Hatuikulipi running Investec Namibia, and Shanghala climbing the ranks of the government.

Outside of work, they went on holidays and to weddings together. They owned houses in Cape Town, bought a farm together, and own houses in a gated community at Finkenstein, an elite residential area east of Windhoek.

The two became practically family.

As they progressed professionally, Shanghala enjoyed the limelight more, basking in the fame of being a politician.

When the two flew together, Shanghala would talk to almost everyone on the plane, while Hatuikulipi often kept a low profile. Those who know them say the more frugal Hatuikulipi, who ran their finances, came across as frustrated at Shanghala’s spending habits.

But they became fiercely protective of those who got close to them – including those they got into romantic relationships with.

RISING STAR

After leaving Geingob’s office in 2001, Shanghala moved to the Ministry of Justice as an adviser to then-minister and attorney general Pendukeni Iivula-Ithana, where he stayed until 2010.

That’s where he first blurred the lines between his jobs as a civil servant, a politician, and a businessman.

In 2004, he and his close friends created a private company that won a contract to supply 50% of the country’s fuel to the state-owned oil company Namcor.

They did this through a black economic empowerment consortium, called Namibia Liquid Fuels.

Shanghala, Hatuikulipi, Hungamo, and Ndutala Angolo (then permanent secretary in the Office of the President) formed a company called Hanganeni Investment Holdings.

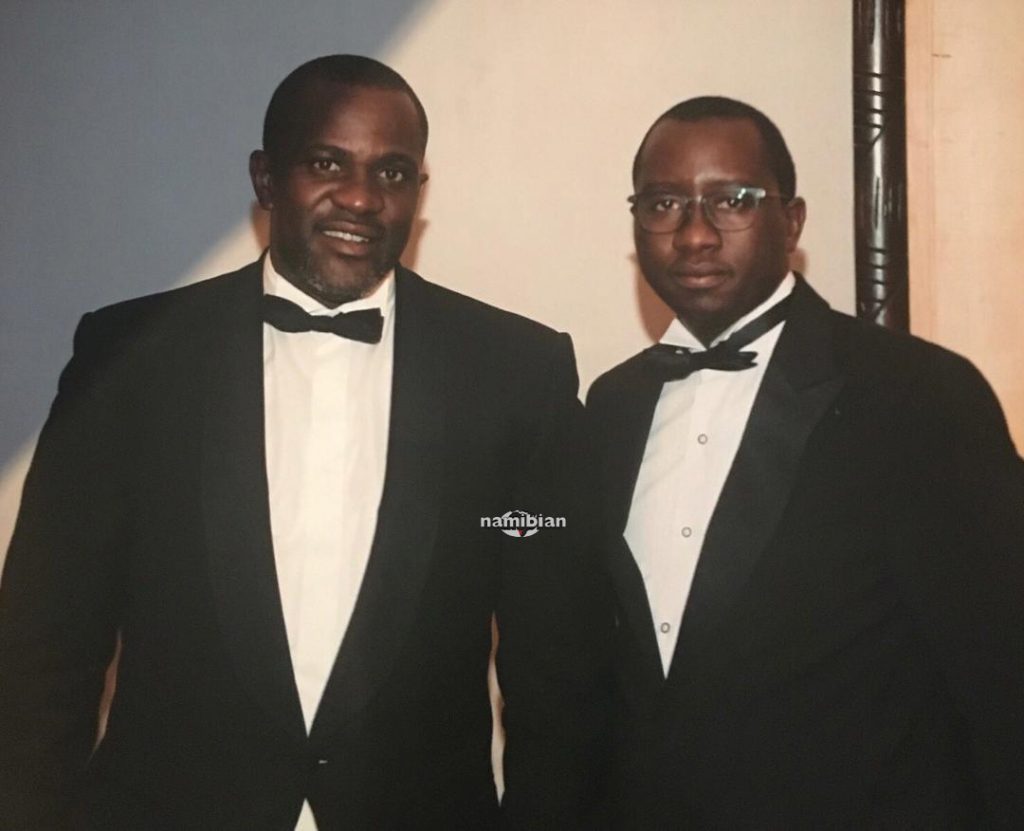

James Hatuikulipi and Sacky Shanghala in court. Photo: The Namibian

It held their shares in Namibia Liquid Fuels, Schoemans Office Systems, and an actuarial firm called Jacques Malan Consultants.

The fuel deal made Shanghala and his partners around N$100 million in five years without breaking a sweat.

Hanganeni would later clinch a lucrative deal with Unam to build and operate hostels at the university.

In 2007, Shanghala was still doing legal work for the government, while also serving in the justice ministry.

Shanghala is said to have cherry-picked legal briefs to work on, and the ministry never explained why he was allowed to keep working as a lawyer.

He wrote the government’s catering guidelines while he owned shares in an airline-catering business.

Shanghala insisted the guidelines affected only schools and hospitals, and had nothing to do with flights.

THE PRINCE

In 2010, Shanghala was appointed chairperson of the Law Reform and Development Commission, tasked with recommending changes to the law.

That job became his springboard to more power and money. He focused on three targets: Swapo, fish, and Geingob.

In November 2012, Shanghala was invited to a State House dinner hosted by former president Hifikepunye Pohamba and Geingob, then Swapo’s vice president.

Each person attending paid at least N$100 000 for what was touted as a ‘pow-wow’ with Swapo’s ‘Top Four’.

Shanghala’s invitation from Swapo deputy secretary general Nangolo Mbumba was sent on 1 November 2012.

“I am delighted to inform you that you have been identified by the leadership of the Swapo party as a vital, respected stakeholder in the Namibian economy,” Mbumba wrote to Shanghala.

The meeting, according to Mbumba, was to discuss developments affecting future government policies. In reality, the meeting was meant to raise funds for Geingob’s political campaign at Swapo’s 2012 congress.

Geingob won the vice presidency, enabling him to succeed Pohamba.

Next, Shanghala used his law reform post to publish a 74-page report called ‘Urgent and Targeted Report on Fisheries’.

That document was shared with fishing companies, lawyers, businessmen, government officials, and Swapo.

Presented as simple reforms to the fishing sector, the report paved the way to the Fishrot scandal.

But there was a threat to Shanghala and minister of fisheries and marine resources Bernhard Esau’s plan: Namsov – a consortium of fishing companies that dominated the sector for decades.

According to Shanghala and Esau, Namsov had made more than N$1,2 billion in profits from state-related fishing concessions in three years.

So in July 2013, when Namsov asked for a quota to catch 100 000 tonnes of fish, the ministry approved only 1 259 tonnes.

Esau diverted the lion’s share to the state-owned National Fishing Corporation of Namibia (Fishcor), even though Fishcor didn’t qualify for the quota.

Namsov dragged Esau and the ministry to court.

That same year, Shanghala was pushing for tighter rules to regulate the media.

‘ONS GAAN VORENTOE, PAPPA’

Shanghala famously declared “ons gaan vorentoe, pappa (we are marching ahead)”, taking a stab at his critics for their corruption allegations.

In the midst of the Namsov fight, he saw another opportunity to make quick money in Angola.

He helped set up a company that acted as a conduit for fishing quotas donated by Namibia to the Angolan government.

Minutes from a 2014 meeting show that Shanghala played double roles – as a state official negotiating for the government, and as a businessman representing a company that would benefit from the deal.

The proposed scheme would see Namibia donate N$150 million of fish to Angola.

But the fish would not go to Angola.

Instead, it went to Namgomar Namibia, a company managed by Ricardo Gustavo, one of Hatuikulipi’s colleagues at Investec Asset Management Namibia (now known as Ninety One Asset Management).

Documents show that Shanghala sent a celebratory email on 26 February 2014.

“Gentlemen, we are in business,” he told his Icelandic and Namibian business partners of the Angolan deal.

Around August, Shanghala and Hatuikulipi travelled to Iceland to woo investors from one of the world’s biggest fishing companies, Samherji.

“The opportunity we have in Angola and Namibia is not available to everyone. Before everyone wakes up, we need to move and make [an] impact. This will protect both ministers,” Shanghala said.

On 3 December 2014, Windhoek High Court judge Shafimana Ueitele delivered Shanghala a setback.

He ruled that Esau acted unconstitutionally by depriving Namsov of fishing quotas.

In practical terms, that meant little. The quota was already used.

But the judgement rattled Shanghala, who then changed the fisheries law to allow Esau to dish out fishing quotas through Fishcor at will.

POWER TURNS DESTRUCTIVE

Shanghala also used his law reform position to fast-track unpopular constitutional amendments that increased the number of parliamentarians, and created a vice president position.

Former justice minister Sacky Shangal

When Geingob became president in March 2015, he named Shanghala attorney general.

Some saw it as a reward for delivering the constitutional amendments in just five weeks.

Others feared that Shanghala could be a poisoned chalice in the new administration, which had promised to fight widespread corruption.

‘Sacky’ or ‘Mazo’, as he is called among his peers, hit the ground running, and got busy working on reforming laws – mostly for his benefit.

In his first speech in parliament, Shanghala promised he would carry out his duties without fear or favour, and in the national interest – a promise that would haunt him later.

Shanghala’s drive and appetite for asserting his authority made him a powerhouse in the Cabinet.

In July 2015, Shanghala’s office took on more powers, vetting every state contract.

It emerged later that Shanghala used this process to either enable questionable state contracts worth billions of dollars, or to bluntly favour his business partners and friends.

In some cases, he is accused of turning a blind eye to blatant corruption.

Within just one year of becoming attorney general, Shanghala was embroiled in controversial deals, such as the Kora Music Awards.

The government paid businessman Ernest Adjovi N$23 million to organise the Kora All Music Awards in 2015. The awards never took place.

At the time, a lawyer warned the government that year that the Kora contract, facilitated by Shanghala, had several loopholes and an illegal clause.

Shanghala was intimately involved in the Ovaherero/Nama genocide negotiations with Germany. He paid N$36 million to United Kingdom lawyers to advise on the government’s reparations demand against Germany for the 1904 to 1908 Nama and Ovaherero genocide.

Late in 2015, Shanghala had to defend himself and his office in parliament against allegations that he had received N$3 million in kickbacks during the settlement of the discontinued mass housing contracts.

BUYING POWER

The year 2016 was a busy year for Shanghala, for questionable reasons.

He worked on reforming the Government Institutions Pension Fund (GIPF), in which Hatuikulipi had an interest via Investec.

It manages a large chunk of civil servants’ pension money – N$16 billion of the N$120 billion in the GIPF’s portfolio.

That same year, the Ministry of Works and Transport questioned an open-ended agreement between TransNamib and D&M Rail for the rehabilitation of the Kranzberg-Tsumeb railway line, a deal worth N$100 million a year.

D&M Rail was owned by Hatuikulipi and businessman John Walenga.

The works ministry had approached Shanghala’s attorney general office for advice about the validity of the agreement.

Despite his conflict of interest through his business partnership with Hatuikulipi, Shanghala told the works ministry it could not end the contract.

Shanghala also helped create the controversial state-owned diamond company Namdia, and approved the creation of a valuation company called C-Sixty Investments, owned by Hatuikulipi’s partner, Walenga.

A few days after Christmas in 2016, in the VIP area of the posh Shimmy Beach Club in Cape Town, Shanghala and Hatuikulipi sat with Adriaan Louw, a Namibian businessman with decades of experience in southern Africa’s fishing sector. At the time, Hatuikulipi was Fishcor’s chairman.

There they formulated the first stages of a scheme that would allegedly channel millions of dollars from Namibia’s fishing industry to Swapo and keep Geingob in power.

The alleged stolen money would come from Fishcor, which received fishing quotas from Esau.

From there, more than N$75 million was transferred to a law firm run by Shanghala’s personal lawyer, Marén de Klerk.

The following year, Shanghala sent the lawyer who set up Celax a list of 17 recipients who had performed services for Swapo and were to receive transfers from the company.

Bank records and emails show that the former justice minister called the shots on some payments towards Geingob’s party campaign.

Shanghala earned a reputation as a financier of Swapo events. He often chipped in to pay for costs such as accommodation, entertainment, and even allowances for factions aligned to Geingob, using alleged stolen funds.

Amid all the controversies, some lauded his work ethic.

“Sacky would push us to the maximum to get it done. It was exhausting, but many of my colleagues will tell you it has taught us a lot,” one of his former colleagues says.

Shanghala has also helped some young lawyers travel abroad for further studies.

Many of them saw him as the face of a new kind of legal brain who would propel Namibia to a brighter future.

But there were concerns that Shanghala was using young lawyers to enrich himself for doing his bidding in dodgy deals, such as the Kora Music Awards. Some young lawyers started living large with expensive houses and vehicles.

They have privately admitted that they may be arrested.

In 2017, Shanghala proposed criminal immunity from prosecution for ministers.

In all the controversies, Shanghala’s role was the same. He was an organiser and a facilitator who changed laws and policies to benefit himself and those around him.

Shanghala has always maintained his innocence throughout the scandals, and none of them stopped his political rise.

Until he was arrested in 2019 as part of what is now known as the Fishrot corruption scandal.

Shanghala is now set to spend his third Christmas behind bars, facing a corruption and money laundering trial that could last years.

The father of two was planning on getting married before his arrest. But his legacy will always be tainted with allegations of corruption.

In his bail application last month, Shanghala said he is not guilty of any crime and intends to stand trial.

“I have been a faithful servant of this country for some 10 years. I have already indicated the positions in which I served the country. Despite this, grave doubts have been cast on my character,” he said.

Banned from travelling to the United States, Shanghala’s political career has been ruined by money and power.

“It’s a pity things have turned out the way they have,” says one of Shanghala’s ex-colleagues.

“He was definitely an asset for the country – if he had stuck to serving Namibia and not his own interests.”

- This article was produced by The Namibian’s investigative unit. Email us news tips from your secure email to investigations@namibian.com.na

– Additional reporting by Shinovene Immanuel and Mathias Haufiku