By Sonja Smith | 7 May 2021

WINDHOEK, Katima Mulilo, Walvis Bay and Rundu rank highest as the towns where men have been falsely accused of being fathers in the past four years.

This is according to statistics the Office of the Judiciary released last month.

Many men’s worst nightmare is raising a child and finding out it is not theirs.

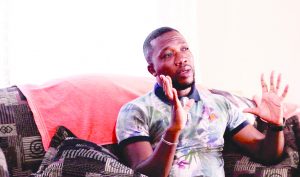

This happened to Phillipus Amunyela twice.

Amunyela (33) raised two children for seven years before discovering he was not their biological father.

The public relations officer spoke to The Namibian about the heartbreak of raising two children who were not his.

He says it all started in 2011 when he found himself in a long-distance relationship.

In May that year his girlfriend claimed she was pregnant.

Five months later she told him she had to see a doctor due to an emergency.

The foetus’ umbilical cord was allegedly damaged, and could no longer supply it with nutrition and oxygen.

“So they had to take the child out,” Amunyela says.

“As a new father, I did everything for my daughter. I put her on my medical aid, and took out a study policy,” he says.

He says he later told a friend his child was born at five months.

But his friend was sceptical and suggested the child was not his.

“That triggered me. We went for a paternity test and the results came back negative,” Amunyela says.

He says he felt humiliated. In 2015, he started dating again.

In May that year, his new girlfriend told him she was pregnant with his child.

Amunyela says he took responsibility for the pregnancy, but the couple decided to end their relationship.

“I named the child, completed his birth certificate, and put him on my medical aid. This time, I really thought this was my child,” he says.

Each month, he would send the child’s mother money, he says.

However, the parents’ relationship soon soured.

“She wanted the child to go to an expensive school, and I told her I could not afford it,” Amunyela says.

A slip of the tongue by his ex-girlfriend led Amunyela to undertake a paternity test.

“We argued over something, then she said the child does not look like me, and that he was not mine,” he says.

He says the boy’s mother apologised the next day, saying she was joking.

“I went for a paternity test, which came out negative,” Amunyela says.

WHO’S THE DADDY?

Yvette Husselmann, the spokesperson for the Office of the Judiciary, says between January 2018 and April 2021 some 130 cases at the Windhoek Magistrate’s Court’s maintenance court were referred for paternity testing.

Of these, 54 identified fathers were indeed not the children’s biological fathers.

Between June and July in 2018, a total of 34 cases of false paternity were confirmed at maintenance courts across the country.

Katima Mulilo recorded 48 cases from 2015 to date, 19 of which proved negative.

In 2016, Women’s Action for Development reported that 70 out of 182 disputed paternity cases involved false claims.

Experts have raised concerns over the fact that Namibians from poor backgrounds are unable to afford paternity tests.

The Maintenance Act states that a man can request a paternity test if he is asked to pay maintenance for a child but believes he is not the child’s father.

MORE LIES

Shampapi Linyando (35) from Mabushe village in the Kavango East region got married in 2010 and had two boys.

“In 2018, she told me the children were not mine, and even went ahead to tell me who their biological father was,” Linyando says.

He says he supported the children financially and otherwise.

“I gave them my all. I was upset and felt bad, but I did not take any action against her. We are divorced now,” he says.

Godwin Kauaaka (41) from Epukiro says his girlfriend told him 17 years ago their son was not his.

He says it has made him more cautious of romantic relationships.

Kauaaka says at the time he was already separated from the child’s mother.

“I did not put up a fight, or claim what I’ve spent on maintaining her and the child. I told her to remove my name from the birth certificate so that there are no complications,” he says.

Sadly, the child died two years later.

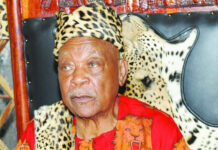

Dineinge Sheya (70), secretary to the Oukwanyama queen, says his experience ended his marriage of 20 years.

Sheya used to be the principal of the Haimbili Haufiku Senior Secondary School.

“In 2019, we filed for divorce after my ex-wife told me she was tired of me and that our son was not really mine, but another man’s child. We had two children,” Sheya says.

After raising the children for years, she has now also refused him access to them, he says.

MOTIVES

Human rights activist Rosa Namises says some of the reasons why women deceive men into taking care of other men’s children are status, money and family background.

Namises, who is also the director of Women Solidarity Namibia, says romantic relationships used to be based on understanding and trust – not money.

“We have discovered that our women are registering children with the wrong fathers, and this has affected many children in the long run,” she says.

Women are also often driven to deceiving men who are wealthy or simply employed, she says.

She says Namibian laws do not protect men as much as women.

The law should cease to solely make women the party to identify a child’s father, Namises says.

She urges Namibian men to break the silence and speak out on paternity fraud.

“The situation creates anger, shame, and the feeling of being abused and used . . . our men are very angry, and therefore they tend to either kill the child or the woman or themselves,” Namises says.

LEGAL ROUTE

Paternity tests in Namibia cost between N$2 500 and N$3 000 and take 14 days before results are available.

The test requires blood or saliva samples from the child and the parent in question.

Lawyer Silas-Kishi Shakumu says men who are victims of paternity fraud can take legal action to recover their financial losses due to raising a child.

He says the most suitable litigation path would be a civil process, but warned it is costly.

“In the end, the aggrieved man would have to choose between going after the parents of the child and incurring litigation costs, or abandoning possible civil claims against them and be the loser in the process,” Shakumu says.

CHILDLESS

University of Namibia sociology lecturer Ndeshi Namupala says childless relationships sometimes drive women to get pregnant elsewhere to prove that they are fertile.

“A childless marriage is blamed on a woman, even in cases where the fertility problems could be from the man. In most cultures, marriage is viewed as incomplete if it does not produce any biological child,” Namupala says.

“The onus is on the woman to prove she is fertile, and as such, she may get pregnant elsewhere to protect herself, and sometimes even her partner,” Namupala says.

She says in some cases women do not realise they are expecting a child before entering a new relationship.

“Sometimes it is a mother who misidentified paternity. It could mean she was in a relationship which ended, and then started a new one. She may have been unaware that she was pregnant from the previous relationship and engages in the new one,” Namupala says.

She says misidentification is dangerous not only to biological and those men who are not, but also to the children and families involved.

She calls for paternity tests to be done free of charge as they are “expensive and many Namibians cannot afford them”.