By Timo Shihepo and Sonja Smith

WHEN former Cabinet minister Erkki Nghimtina filed for divorce, he never expected that the process would take six years – and that even then he would still be haggling over how to divvy up property with his ex-wife.

“It’s supposed to be simple to just say: ‘Look, our love has expired to an extent that we can no longer be together anymore,’” he said. “Then we parted ways. But it is not. It’s more complicated.”

Nghimtina declined to say how much he had spent on legal fees, but spoke admiringly of Cuba’s famously simple divorce laws. Cuban couples have reported getting a divorce in about 20 minutes, at the cost of around N$15.

“In Cuba, if you marry… and you feel you no longer want the person, you can divorce without any issues,” the 74-year-old said.

Nghimtina believes that lawyers often lie to their clients in order to prolong cases, while raking money in through legal fees. He said the law should make divorce a much simpler process, and focus more on the maintenance of children born within the marriage.

Now living in norther Namibia, former defence minister Charles Namoloh, who is seeking divorce from his wife of 25 years, agreed that court proceedings are drawn out and complicated.

“The court is slow, absolutely slow and the process is expensive. You can’t go to court without a lawyer. The process is really cumbersome. I spent a lot of money,” Namoloh told The Namibian yesterday.

There’s no doubt the divorce process can be draining.

Jackie Wilson-Asheeke told The Namibian last year that divorcing her husband of 33 years only brought her more headaches and heartache.

The former chairperson of Namibia Wildlife Resorts was married in community property, meaning all of the couple’s assets were legally shared – even those acquired before the marriage.

She started divorce proceedings in September 2018.

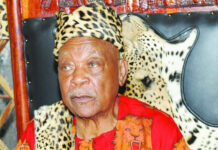

Erkki Nghimtina.

N$55 000 later, and the process was only finished in January 2021, after failed mediation, endless court dates and agonising encounters with lawyers who charged inexplicable fees, all to get a divorce that both parties wanted.

“It was nearly two and a half years of lawyers, frustration, anxiety, worries about my children, emotional depression, angst, uncertainty, insensitive comments by all kinds of people, including family and friends, tears, painful memories, and finally, blessed relief,” she said.

Wilson-Asheeke’s ex-husband declined to comment.

Namibia still uses a fault-based divorce law inherited from apartheid South Africa at independence – a system South Africa itself no longer uses.

That means that if a couple wants to divorce, one of them has to prove that the other violated the marital contract.

Cruelty, adultery, and desertion are common examples of grounds for a fault divorce.

In contrast, no-fault divorces do not require any showing of wrongdoing. Rather, the filing spouse simply claims that the couple cannot get along and the marriage has broken down.

Proving wrongdoing in court is time-consuming and expensive, requiring lawyers to argue cases.

“Couples who lack the financial resources necessary to open divorce cases at the High Court are forced to remain in broken marriages,” justice minister Yvonne Dausab said.

Justice minister Yvonne Dausab

“Others opt to just separate as a means of avoiding the high cost of divorced.

“The current divorce legislation renders divorce in Namibia too expensive an undertaking for those who cannot afford legal representation,” Dausab added.

The Namibia Legal Information Institute said as far back as 2013 that the divorce law is outdated and may violate the Constitution’s Article 8 protections providing for the dignity of all people.

DRAINING

Loide Shilongo (49) from Engela has just emerged from an 18-month divorce process, although she admits that she dragged the process out by ignoring court papers.

Shilongo says that after 21 years of marriage, her husband simply woke up one morning to tell her that he no longer loved her.

“He told me that he didn’t want to be married anymore. I didn’t understand it. And he wouldn’t tell me why he didn’t want to be with me anymore.”

After she demanded clear answers, he opened up and confessed that he had fathered a child out of wedlock.

“The child was seven years old,” Shilongo said.

But she forgave him.

“Maybe I wronged him in some ways.”

Two months after the divorce was finalised, her husband remarried.

Meanwhile, to compound her loss, she lost three properties during the court process – two in the northern region and one at Walvis Bay.

“We started from nothing,” Shilongo said. “He was a bus driver at first, then joined the police. I found a job in the early 2000s and we built everything together.

“It was shameful for me. You don’t even want to see your neighbours or speak to family. It’s embarrassing and damaging to have to start all over again.”

She believes the law should require counselling to help couples through this emotionally draining process.

CASHING IN ON DIVORCE

The case of Matthew Andreas* (not his real name) is somehow different.

The 36-year-old married his childhood sweetheart in 2011 in a flashy wedding ceremony.

He expected a blissful marriage for life.

Three years later, that dream did not just crumble, it vanished altogether, leaving Andreas more than N$300 000 in debt as he tried to legally separate from his wife.

The debt emanated from legal costs after he hired a law firm to represent him in a case that saw his partner demand N$4 million.

The divorce case started in 2014 but was only concluded in 2017.

CASES ON THE RISE

The courts are finding it increasingly difficult to cope with the escalating number of divorce cases.

In 2018 alone, the Windhoek and northern division courts handled 1 442 divorce cases. While 1 297 were finalised that year, 45 were withdrawn. The following year, another 1 422 cases were filed, but only 862 were finalised.

Divorce lawyer Sifiso Nyathi said divorce matters normally become hostile when parties contest the division of property or the custody of minor children.

“My worst experience was when I attended a divorce mediation, with my client being the husband,” said Nyathi.

“The mediation started on a good note until there was disagreement between the parties in respect of the custody of the children. The client then stood up and flipped over the round table at which the parties were seated. The client was disgruntled by the fact that his wife wanted to terminate his parental rights over the children.”

To reduce the backlog and speed up the process, Nyathi said lower courts should be allowed to handle divorces.

Currently, only the High Court handles them, while appeals go to the Supreme Court.

“It is about time the grounds for divorce are amended to include irretrievable breakdown of a marriage, as is the case now with our neighbouring country, South Africa,” he said.

Nyathi added that moving the divorce process to the lower courts, especially where assets are owned separately and the spouses both want to split, would make the process faster and cheaper.

“But cases with complex financial or custody issues should remain at the High Court,” he said.

REFORM

Namibia has started thinking about reforms.

A Cabinet directive of 6 September 2019, seen by The Namibian, endorses the recommendations of a study regarding Namibia’s current fault-based grounds for divorce.

“The Cabinet endorses the divorce report and forwards it to the National Assembly for the promulgation of the divorce bill, which repeals the divorce laws for the amendment ordinance, the matrimonial causes jurisdiction,” said secretary to Cabinet George Simataa, in a letter.

These recommendations seek to replace the fault-based grounds for divorce with the easier claim of an irretrievable breakdown of the marriage.

The changes recognise that requiring one person to prove the other spouse’s guilt may lead to collusion, the giving of false testimony, or increased anger.

The divorce report recommends a simplified procedure, requiring, for instance, that summons be worded in clear and simple language. Other recommendations include abolishing the current requirement that a divorce cannot in most cases be granted unless the spouse first obtains a restitution order compelling the partner to resume the marriage within a certain time period.

The changes seek to eliminate the delay and additional costs that arise from the restitution order requirement.

Dausab said the proposed divorce bill is expected to simplify divorce proceedings and reduce costs.

She said no-fault divorce reduces the need for costly litigation to determine who is to blame for the failure of a marriage.

“In a no-fault system, spouses are more likely to agree on the terms of the divorce and so eliminate the need for lengthy court proceedings and costly legal representation,” she said.

Information at hand shows that the proposed no-fault divorce regime will allow spouses to terminate their marriage more amicably, cheaply and, hopefully, each party will go on to live happily ever after.

- This article was produced by The Namibian’s Investigative Unit. Send story tips via your secure email to investigations@namibian.com.na